Background Information

Bubonic Plague

Bubonic plague is a potentially fatal bacterial infection caused by Yersinia pestis. Further description of Y. pestis is provided below. There have been several outbreaks of bubonic plague throughout history with the first outbreak in Europe possibly lasting for roughly 200 years. There was then a 600 year break from the plague before it returned as the Black Death. 1 There have been three great pandemics of bubonic plague in the past 2,000 years. 2 The first, the Justinian plague, named after the Emperor Justinian, occurred in 542 and struck Constantinople with a vengeance. It killed 10,000 people per day at its height and held the city of Constantinople in its suffocating grip for a full year. Emperor Constantine was unable to keep the newly united Western and Eastern Empires intact. The loss of over 100 million people to the plague left no one to carry out the essential tasks of a large empire. 3 Between the years 541-700, an estimated 50-60% of the population of the affected area was eliminated. 4 The second outbreak, the Black Death, is the one we will focus on in this unit. The third began in China in the 1860s and we are still dealing with a less virulent form today. 5

The Second Outbreak OR the Black Death

There are two ideas as to why the second pandemic of bubonic plague was referred to as the Black Death. One idea set forth is that it was named for the gangrene that set in before people died. On the other hand, it could also be a mistranslation of atra mors. The Latin word, atra, can either mean "terrible" or "black". Regardless of the reason the bubonic plague came to be known as the Black Death, it was indeed terrible and enshrouded Europe in darkness. This second great outbreak seems to have started with the siege on Kaffa, a Genoese city located on the Black Sea, by the Mongols in 1347. The Mongolian army began to succumb to a terrible illness and was forced to give up the siege and leave the area. As the story goes, before they left their encampment outside the city wall, they catapulted the bodies of the infected soldiers into the city. The Italian inhabitants left for home and twelve galleys set sail for the Sicilian island, to the city of Messina. These ships were carrying the Black Death. 6 The following is a first hand account of a Franciscan friar, Michael of Piazza:

The "burn blisters" appeared, and boils developed in different parts of the body: in the sexual organs, in others on the thighs, or on the arm, and in others on the neck. At first these were of the size of a hazelnut and the patient was seized by violent shivering fits, which soon rendered him so weak that he could no longer stand upright, but was forced to lie on his bed, consumed by a violent fever and overcome by great tribulation. Soon the boils grew to the size of a walnut, then to that of a hen's egg or a goose's egg, and they were exceedingly painful, and irritated the body, causing it to vomit blood by vitiating the juices. The blood rose from the affected lungs to the throat, producing a putrefying and ultimately decomposing effect on the whole body. The sickness lasted three days, and on the fourth, at the latest, the patient succumbed. 7

The terrified people in Messina fled to Genoa and Venice. Soon after, it was traveling along the trade routes of the day. Once in a city or village, it generally lasted eight months until the unlucky ones died a horrific death or those that were going to be fortunate enough to survive, recovered. The Black Death reached Spain, France, and the Mediterranean Islands in 1347-48 and was in Britain by the summer of 1348. By the end of that year, 20,000-30,000 of the 60,000-70,000 inhabitants of London were dead. 8 The plague was so devastating to Europe at that time because it hadn't been in Europe for over 1,000 years. People who have been exposed to the plague and recover gain resistance, and therefore do not become sick again when the plague returns. Since no one had been exposed in recent years, no one had any immunity to the disease. This second great outbreak of bubonic plague had finally run its course by 1353. It continued to ebb and flow over Europe for the next 300 years. Even though the mode of transmission at this time was unknown, preventative measures to stop the spread of the disease began to develop. For example, a 40-day quarantine, "quaranta giorni", was introduced in Italy and later widely practiced throughout Europe. 9 By the time the plague dissipated in 1352, it had killed 20 million people in Europe and the Middle East, reducing the population to 80 million. 10

Yersinia pestis

Yersinia pestis, the bubonic plague causing bacteria, is a Gram negative, nonmotile, oval-shaped bacteria. It is a coccobacillus, meaning that it has a shape somewhere between that of a sperical form, coccus, and a rod-shaped form, bacillus. 11 Of the 11 members of the genus Yersinia, only three are pathogenic, disease causing, in humans. Yersinia pestis is the one of concern here and it establishes itself in the blood and lymphoid tissues and has evolved to be capable of being transmitted by arthropods and in the case of the Black Death, most commonly by fleas. 12 Y. pestis has two unique plasmids, pFra and pPla, that contain genes allowing it to not only infect mammalian hosts but also to spread between them. These genes also allow Y. pestis to use fleas as a vector. These differing genes get expressed based on the differing internal environments of their hosts, 98.6Ú F in mammals and 82.4Ú F or lower in fleas. Other genes located on these plasmids allow the bacteria to hide out from the host's immune system while it prepares for its all-out assault. 13

Method of Transmission

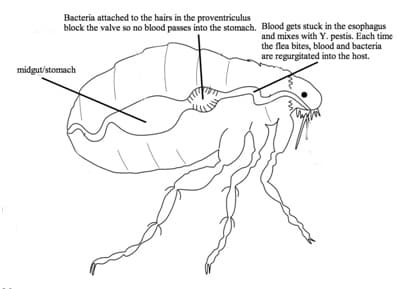

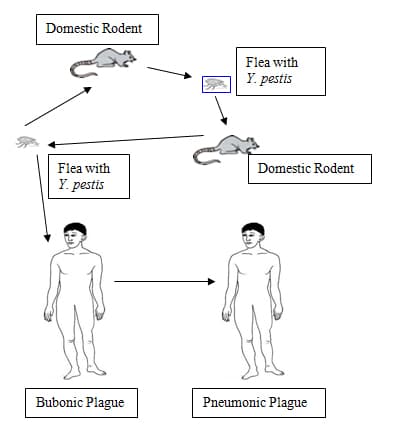

Different species of fleas show different methods of transmission in different mammals. However, the method discussed for this unit is common in the Oriental rat flea, Xenopsylla cheopsis. 14 It is thought that the black rat, Rattus rattus, has the unlucky distinction of being the vector for X. cheopsis during the Black Death. It is, as rats go, not very hardy. Its original homeland was in the Himalayan foothills but populations were well-established in warmer areas, such as North Africa, by the beginning of the Christian era. From there, they were able to hitch rides all along the various trade routes. They spread rapidly throughout Europe and were able to establish themselves by living closely with humans, infesting barns, graneries, and thatched roofs. When Y. pestis moves through a colony of rats, the rats die rather quickly. Once the colony is exhausted, the fleas are then able to jump to humans. X. cheopis has a valve to its stomach that allows its stomach to become distended with blood after feeding without regurgitating the next time it feeds. This allows the flea to keep biting and feeding even though its stomach is "full". In a flea that has ingested Y. pestis, the bacteria multiply rapidly and form a ball of blood and bacteria that render the valve ineffective. The next time the flea feeds, the blood is unable to pass into the stomach and remains in the esophagus. There it mixes with bacteria and the next time the flea attempts to feed, the blood and bacteria mixture are regurgitated into the next victim. The still hungry flea then bites another victim and more blood and bacteria enter that victim. This keeps happening until the by now very frustrated flea starves to death. Even if the fleas are on rats on quarantined ships and all the rats die, the fleas can survive rather long periods of time if conditions are cool and damp. 15

Infection Cycle

Once Y. pestis bacteria are introduced into the skin of its new, human host, they make their way to local lymph nodes. Here the inflammatory response, the swelling of the lymph nodes producing the characteristic buboes, can delay the spread and rapid increase in the number of Y. pestis; however, it generally doesn't completely block the disease. The spread of Y. pestis from the site of the bite is facilitated by Pla protease, a virulence factor, which breaks down the components of blood clots that would normally help trap the bacteria at the site. Then another protein, F1 protein, prevents phagocytosis of Y. pestis by white blood cells as the bacteria initially spread through host tissues. The bacteria are able to spread swiftly to invade visceral organs, such as the liver and spleen. Once there, the host's immune system is further blocked by yet more virulence factors. Several of these virulence factors prevent the host's immune system from launching an all out attack. Y. pestis uses a needlelike appendage to target and inject proteins into the host's white blood cells. The immune functions that would normally trigger an inflammatory response to help block the spread of the bacteria are destroyed by these proteins. Furthermore, another injected protein, V protein, prevents the host from producing the proteins necessary to trigger the formation of a mass of immune cells that would normally surround the bacteria and inhibit its growth. In this way, Y. pestis is able to quickly overrun visceral organs even though the host cells believe that tissue damage is totally under control. 16 Bleeding into the organs causes the skin hemorrhages commonly seen in the Black Death. This type of death lasts four to five days; however, if a flea bites a tiny blood vessel, death occurs within hours. Sometimes Y. pestis gets into the lungs and causes the victim to cough up bloody sputum teeming with bacteria. Y. pestis is easily transmitted via airborne droplets. Those unlucky enough to inhale the bacteria in these aerosols come down with primary pneumonic plague, which is universally fatal. 17

Current Plague Control

Attempts at plague control involve testing die-offs and wild populations that commonly harbor the bacteria, such as rats and prairie dogs, for Y. pestis. If the bacteria are found, the public is notified so that caution is used in the area. Treating rodent burrows to kill fleas and trying to limit the desire of rodents to be in residential areas are two common ways to combat the spread of the plague. Ridding the world of the plague is not an obtainable goal because of the continuous outbreaks in animals other than humans. Infection can even be transmitted from house pets that have been in contact with humans. Humans, especially veterinarians, have experienced an increase in pneumatic plague due to exposure to infected cats. 18

Diagnosis, Treatment, and Vaccination

Diagnosis of plague hasn't changed since its discovery. Physicians Gram stain and culture sputum or bubo aspirates. Y. pestis can be grown on blood agar and MacConkey agar in the lab. Human disease is rare, but airline passengers who have been to a known plague region and are feverish should be placed in isolation. A plague-infected person's condition can deteriorate quickly. If left untreated, death can occur in three to five days and the overall mortality rate for untreated plague is still more than 50%. Antibiotics readily available for treating the plague include streptomycin, gentamycin, sulfonamide, and tetracycline, and tetracycline and chloramphenicol can even be used prophylactically. Fortunately, there have been no reports of antibiotic resistance. The first vaccine for bubonic plague was developed by Waldemar Haffkine in 1897 in Bombay using dead bacilli. There are now two types of vaccines used in humans. One is a live vaccine that has been used in the former Soviet Union since 1939 and one is a formaldehyde-killed whole-cell vaccine. The latter vaccine was first used in 1942. There is a new vaccine under development which uses the F1 and V bacterial capsular antigens. 19

With Bubonic Plague Comes Change

Even though the Black Death was the worst plague outbreak in Europe, the waves of the plague continued to sweep through. Every two to five years from 1361-1480 there was another outbreak in England. The following is a list of cities, dates, and populations lost:

Milan, 1630, half the population lost; Genoa, 1656-1657, 60% lost; Marseilles, 1720, 30% lost; London, 1665, 16% lost (70,000 lost). 20

Some of the most heinous atrocities occurred during the successive waves of plague that ravaged Europe. Lepers, beggars, prostitutes, and Jews were all blamed for the plague. In some Muslim countries, the Christians were blamed. Both Christians and Muslims almost always blamed the Jews. In Strasbourg, February 14, 1349, 900 Jews were rounded up and burned on the grounds of the Jewish cemetery. This was fully half the total population of the community. All Jews in Freiborg were placed in a wooden building and burned to death. 21 The wholesale slaughter of Jews in Frankfurt and Brussels occurred in 1349. Between the Black Death itself and the just as virulent anti-Semitism, the Jewish communities in many parts of Europe were eradicated. 22

As one can well imagine, in cities where more than 500 people were dying every day, many lost faith in the clergy. Papal authority declined and the Roman Catholic Church blamed the sinners and suggested that Judgment Day had arrived. God didn't even spare his servants and priests, as those who gave last rites had a very high mortality. Fear led to a greater interest in other religions, including in the cults of healer saints. The saints were familiar with suffering and could also provide comfort and healing. People bypassed God and went directly to the saints. The stage was set for questioning church authority and the divisive debates over the nature of religion had begun. 23

As the disease swept through Europe, the holders of the chairs of some of the great universities died. These scholars were generally older and were academics who never really practiced medicine. They were followers of Galen, who believed that diseases were caused by an imbalance of the four humors: blood, phlegm, black bile, and yellow bile. After the old guard died, the newer appointees began moving into more clinical areas, such as anatomy. Barbers, with their ability for bloodletting and skilled surgery, gained new prestige. A new importance on health and disease started to replace the old thinking and ever so slowly, the practice of medicine began to change. 24

As the plague indiscriminately felled its victims, the number of educated individuals decreased as did the number of students. By the end of the plague, Europe had lost five of its 30 universities. With the restrictions placed on travel, students couldn't enroll in distant universities; therefore, local universities were established. It was no longer necessary to travel to Paris or Bologna as new universities popped up in cities such as Vienna, Prague, and Heidelberg. This led to curriculum reform as the dominance of old centers of learning diminished. Because the universities were now local, instruction was in the local language. 25

The Black Death eventually led to the ending of the Hundred Years War as France and England had to quit fighting. Even without the loss of life due to battle, the plague decimated the ranks and left no able-bodied men to fight. Soldiers began getting paid more to remain in service, and without enough men to fight, more efficient ways of killing and causing destruction were developed. 26

By the time the Black Death swept through Europe the feudal system had already begun to change. The switch to monetary compensation for serfs' manual labor happened before Y. pestis became part of the landscape. However, with the continuing loss of laborers, landlords were forced to allow their stewards to start recruiting and paying peasants from other farms and even landless city-dwellers to work the land. The landlords were then not making as much profit and so they kept acquiring more and more land to work to make up the difference. This led to less labor-intensive farming practices. The mould board plough was developed at this time and much of the farmland was converted to pastureland. This led to entire swaths of land being left to the sheep. Mills once used for grinding grains such as wheat and barley were converted to spinning cloth, operating large bellows for fanning furnaces, and sawing lumber. Tenant farmers raising sheep became more prosperous than they'd ever been and more powerful than any sheep farmers before then. These people eventually became the great wool barons of the time. The barons and landlords were forced to treat their tenants better and pay them more. If they didn't, the competition for laborers was high and the laborers could easily find a better landlord. The reduced workforce in the now sparsely populated cities also started receiving higher wages and as a consequence, the standard of living also improved in the cities. Besides there being a reduced population in the cities, wealthy landlords were able to pay even higher wages and convinced many city dwellers to move to the country to work their fields. Now, for the first time, people were mobile. They were no longer tied for their entire lives to working one plot of land. As wages increased, governments sought to control the higher wages and increase taxes. This led to creative thinking on the part of the workers. Cheap lands and other capital were substituted for higher pay. Landlords now had to provide the oxen and seeds before the peasants would agree to a lease. Higher wages and a higher standard of living led to major changes in the social and economic structure. In fact, by the 16 th century, landlords and serfs ceased to exist in England. 27

The substitution of capital for wages was also occurring in the cities. For example, employers might have to provide tools and machines needed for a particular job. Higher wages led to new innovations such as the printing press with movable metal type invented by Johann Gutenberg in 1453. This was necessary because of the lack of good quality scribes needed to copy sheets of manuscripts. In the rush to train new scribes to take the place of the dead ones, the quality of the work kept declining as the emerging population was growing. This rebounding population was increasingly more literate, as well. 28

The last big change caused by the Black Death necessary for this unit is the change to large sea- and ocean-going transport ships. Smaller crews could remain at sea for more extended periods of time and sail directly from port to port on much larger vessels. This required the development of more useful navigational instruments, superior ship building and of course, the development of insurance to protect investments in ships and the cargo. Merchants, bankers, and craftsmen all become more powerful and used their new capital to fund new technological advances. The economy became more diversified and there was a greater redistribution of wealth. The old aristocracy was finding it necessary to yield some of their power to the people. 29

Comments: