Background Information

Models of Fractions

Learning about fractions requires students to think about numbers in a different way than when they work with whole numbers. Students have to understand the relative nature of fractions. That is, fractions express the size of a quantity in relation to a unit, which is given or understood in the context. For example, the same fraction of different units will be different. To get ½ of one egg involves breaking the egg; but ½ of one dozen eggs is 6 whole eggs.

The fact that the larger denominator indicates the smaller piece contradicts what students are used to with whole numbers. For example, 5 is greater than 3, but 1/5 of a cake is less than 1/3 of the same cake. I will give students work comparing unit fractions until I am satisfied that they have absorbed this important but not immediately intuitive fact.

To help students develop an understanding about a fraction they need to be given opportunities to see fractions represented in various models. Through these various representations they will start to understand the relationship between the numerator and the denominator.

Area Models

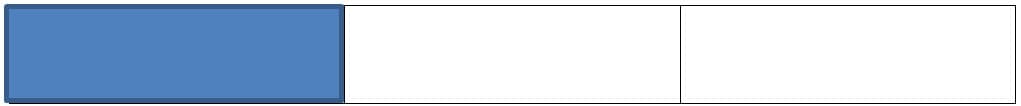

The relationship between the unit fraction and the whole determines how to draw an area model. The use of circular pie pieces, geoboards, paper folding, pattern blocks, and drawings on grids are all good examples of area models. Using these models allows students to partition, or divide, the whole into equal parts. The rectangle below is an area model representing the fraction 1/3 by the shaded region. The denominator tells us that it takes three unit fractions to make the whole.

There are some disadvantages to these models because there can be an issue in how the student interprets shape. Another problem that arises is that students do not have a good understanding of area. This issue can be minimized by the use of grids and strips, but it does not completely eliminate them.

Linear Models

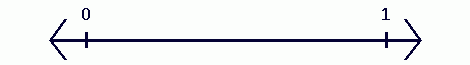

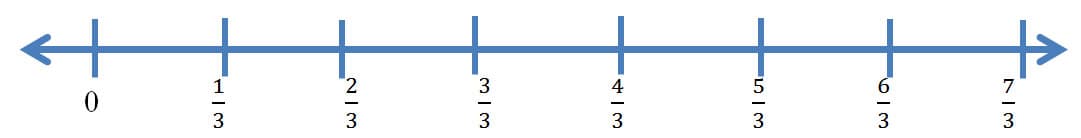

When working with linear models the whole is defined by the unit of distance or length. The use of fraction strips, ruler, and folded paper strips are all examples of linear models. In these models, equal quantities are represented by equal distances or lengths. Using number lines helps students understand a fraction as a number (rather than one numeral over another numeral) and helps develop the other fraction concepts. The use of a number line can reinforce the idea that there is always one more fraction to be found between two fractions and that there are fractions greater than one. The zero is particular to the number line and when using other linear models only the total length matters.

Set Models

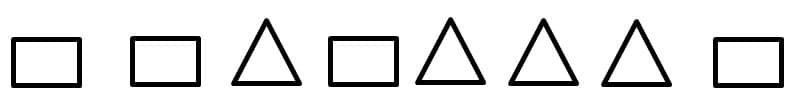

In set models, the whole is determined by the number of objects in the set. This is an opportunity to consider a fraction as a ratio. Then subsets of the whole can be expressed as fractional parts. Fractions can be depicted using this model in many ways. Any countable object can be used as a set model. For example, if 8 shapes make a whole, then a subset of 4 triangles is 4/8 or 1/2.

Division in Fractions

Division is an operation that can be related to fractions in two ways. The idea of partitioning is the process of sectioning a shape into equal-sized parts. This strategy can be used with area, linear, and set models.

Partition with the Area Model

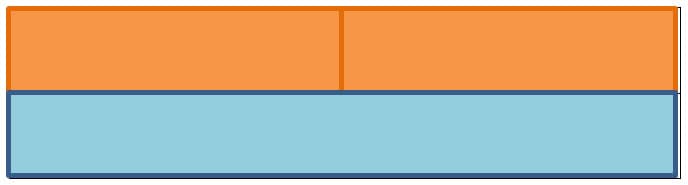

When partitioning an area model it is important to address two main ideas. Students first need to see that fractions may be formed by taking a region and subdivide that into some number of equal pieces. They need to see that some visuals do not show all of the partitions. In the example below, the orange and blue regions each represent half of the whole colored area, although they have been partitioned in different ways. The orange has been further partitioned, and the blue has not. Each part of the orange area is 1/2 of that part, or 1/4 of the whole colored area. Another concept students need to be aware of is that the number of equal-sized parts that can fit into the unit determines the fractional amount. For the example below students need to be able to divide the blue part into two equal parts to see that the small orange partitioned areas would represent one-fourth. Students who don’t have a conceptual understanding may suggest that each of the small partitioned areas represents one-third.

Partition with Linear Models

There are a few things that need to be determined before you start to partition a number line. First, the unit distance must be determined. This can vary from situation to situation. The Measurement principal states: The number labeling a given point tells the distance of that point from the origin/endpoint, as a multiple of the unit distance.

Students need practice labeling number lines in the same fractional increments. This helps students develop the understanding of how general fractions are the multiples of a unit fraction and conceptually understanding that fractions can be greater than one whole.

Partition with Set Models

For example, 12 shapes are partitioned into 4 equal sets – fourths. That would be represented by showing three shapes in each set. Therefore, it is the number of sets that allow us to label each as 1/4, not the number in each set. The second way is through a concept students have learned from a young age, which is sharing. For example, there are 3 people sharing 5 cookies. How many cookies will eat person get? This type of task requires students to think about sharing and also to consider how to share the leftover whole cookies.

Problem Solving

Problem Solving is a process that requires many different skills. As discussed in seminar, the student needs to be able to read and understand the problem. The use of word problems in mathematics can actually help improve the student’s ability to read and comprehend. Therefore, it is important I present various types of problems that expose vocabulary to my students.

Through problem solving we want students to develop a sense of perseverance. This skill will develop as the student works on various problems. When developing problems we want to start with a basic problem that models the structure being used. As students become comfortable then we want to take that problem and add more complexity. The teacher’s role during this process of problem solving is very important. Students need to be presented with a problem and then given time to work through it. So often teachers want to help the students when they start to struggle when really they need to step away and allow them to persevere.

Having a sense of organization is another skill students need to develop. As Polya states, there are steps that should be followed when solving words problems. First, students need to understand the problem. They should be able to make sense of the question and the numbers being used. Then they need to see how the parts of the problem are connected to each other. At this time they can create a plan of action for the problem. After that they can carry out their plan, which may take more than one trial depending on their success. The last step is to look back and discuss the problem. 1 These are steps that will help organize the student’s thinking and allow them to process what the question is asking. For students to become better problem solvers these practices need to be modeled by the teacher.

Taxonomy of Addition and Subtraction Word Problems

In Roger Howe’s seminar—“Problem Solving and the Common Core”—we have discussed how problem solving is a skill that can be taught to our students. We did a great deal of work looking at the various structures of addition and subtraction problems. The taxonomy of addition and subtraction problems can be referenced in the mathematics glossary of the Common Core State Standards, which can be found at http://www.corestandards.org/Math/Content/mathematics-glossary/Table-1/. To construct word problems it is important that the various types and structures are represented.

Through our work in seminar I have learned how important it is to first start with one step problems. First we would create a bank of problems and then share them out to the other fellows. Then each group would read one of their problems aloud and the others would identify the type of problem. This practice made us become more familiar with the different types and we also became more aware of how to write clearer word problems. After our work with one step problems we would start to create two step problems using the same scenarios. We discussed the fact that you can start setting up these problems with whole numbers but you can substitute other numbers, depending on your grade level.

There are three broad classes of one step problems. Those categories are: change, comparison, and part-part-whole.

Change Problems

Change problems have the student look at how things change over time. This change can either show an increase or a decrease in the initial amount. When constructing problems you can change the structure by altering the unknown. These will be the problem types I use in my unit. The chart below shows the different subtypes with some examples:

|

Change increase - result unknown Example: There are 9 pencils in the drawer. Sara placed 2 more pencils in the drawer. How many pencils are now in the drawer? |

Change decrease – result unknown Example: Melanie’s cat had 11 kittens. She gave 4 to her friends. How many kittens does she have left? |

|

Change increase - change unknown Example: There are 9 pencils in the drawer. Sara placed some more in the drawer and now there are 11 pencils. How many pencils did Sara place in the drawer? |

Change decrease – change unknown Example: Melanie’s cat had 11 kittens. She gave some to her friend. She now has 7 kittens left. How many kittens did she have to start with? |

|

Change increase - start unknown Example: There are some pencils in the drawer. Sara added 2 more pencils to the drawer. There are now 11 pencils, how many pencils were in the drawer to start? |

Change decrease – start unknown Example: Melanie’s cat had kittens. She gave 4 to her friends. She now has 7 kittens left. How many kittens did she have to start with? |

Comparison Problems

When working with comparison problems one of the quantities is being compared as more or less as the other. When constructing problems you can change the structure by altering the unknown. The chart below shows the different subtypes:

|

Compare more – difference unknown Example: Tom has 6 pencils. Greg has 10 pencils. How many more pencils does Greg have than Tom? |

Compare less – difference unknown Example: Tom has 6 pencils. Greg has 10 pencils. How many fewer pencils does Tom have then Greg? |

|

Compare more – bigger unknown Example: Greg has 4 more pencils than Tom. Tom has 6 pencils. How Many pencils does Greg have? |

Compare less – bigger unknown Example: Tom has 4 fewer pencils than Greg. Tom has 6 pencils. How many pencils does Greg have? |

|

Compare more – smaller unknown Example: Greg has four more pencils than Tom. Greg has 10 pencils. How many pencils does Tom have? |

Compare less – smaller unknown Example: Tom has 4 fewer pencils than Greg. Greg has 10 pencils. How many pencils does Tom have? |

Part -Part Whole Problems

As the name suggests there will be two parts that when put together form the whole. When constructing problems you can change the structure by altering the unknown. The chart below shows the different subtypes:

|

Part – Part – Whole – total unknown Example: There are 6 daisies and 4 roses in a vase. How many total flowers are in the vase? |

|

Part – Part – Whole – addend unknown Example: There 10 flowers in a vase. Six of them are daises and the rest are roses. How many of the flowers are roses? |

Through discussions, we saw that the “key word” strategy for teaching word problems is doomed to fail. This strategy is not fool proof and will create misconceptions for students. Instead I want them to become careful readers and critical thinkers who are able to understand the problem and what is being asked of them. Often times on assessments, students will be given problems where they can be tricked depending on how the key words are being used. For student success the importance needs to be put on the structure of problems and understanding what information has been given and what is still missing.

When working with fractions it is important that my students understand why the procedures for computations with fractions make sense. It may help for fractions to be put into real life contexts that connect with the students. By personalizing the word problems, I want my students to become more engaged in the process. The context should provide meaning to the fractions quantities being used in the problem and the procedures used to solve it. Using scenarios that focus on school events, such as field trips or class parties, and track and field days can serve as engaging contexts for problems.

In my unit I want to create an environment like the one I had in the seminar. I will give my students practice working with the different problem types. First, I will show them the different structures for change problems using whole numbers and then I will have them substitute those numbers with fractions and mixed numbers. This type of work will demonstrate their depth of understanding and allow me to assess where they are in their learning of the content. My unit will focus on the student’s understanding of change increase and change decrease problems.

Comments: