Contemporary Code-Switching in Native America

Even though Indian boarding schools were closed and tribes began educating their youth on the reservation itself, not all reservation schools are a resounding success like Rough Rock. On some reservations, “white” schools in the border towns still offer an opportunity for a better quality education due to inequalities in funding. These non-reservation schools, however, require American Indian students to code-switch in order to fit in. Sherman Alexie, author of the semi-autobiographical fiction book The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian, details the experiences of Junior, an American Indian living on the Spokane Indian reservation in the state of Washington. He attends school at his reservation school, Wellpinit. Although Junior does not attend an Indian boarding school, his reservation school lacks the funds necessary to provide its students with quality teachers or materials. When he receives his geometry book, he opens it up to see his mother’s name written on the inside, hitting him with the realization that the school materials he is to be learning from are incredibly outdated. He remarks, “My school and my tribe are so poor and sad that we have to study from the same dang books our parents studied from. That is absolutely the saddest thing in the world.”29

His geometry teacher, Mr. P, emotionally tells Junior how American Indians were treated in school when he first began his career, harkening back to the words of Richard Henry Pratt:

When I first started teaching here, that’s what we did to the rowdy ones, you

know? We beat them. That’s how we were taught to teach you. We were

supposed to kill the Indian to save the child… We were supposed to make you

give up being Indian. Your songs and stories and language and dancing.

Everything. We weren’t trying to kill Indian people. We were trying to kill

Indian culture.”30

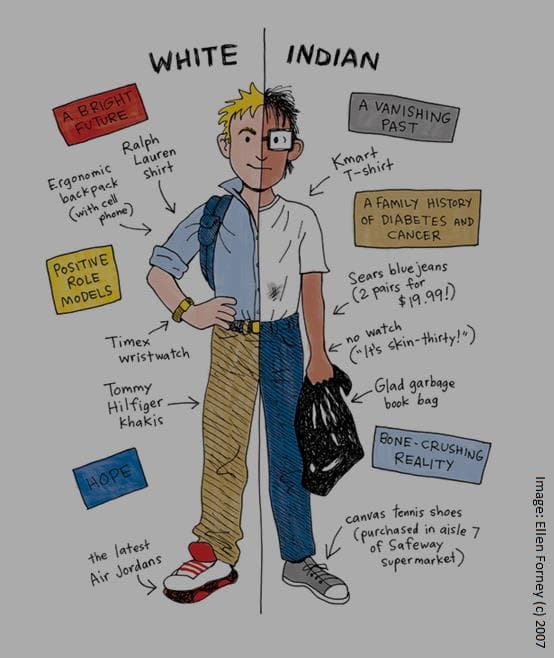

Mr. P also advises Junior that the only way to succeed is by attending the white school in a border town, off the reservation. He pleads with Junior, “We’re all defeated… you have to take your hope and go somewhere where other people have hope.”31 Junior takes his advice, enrolling in Rearden High School where he is the only Indian. He immediately has to begin code-switching from Indian culture to white culture to survive. Junior, known as Arnold at Rearden, describes the culture shock he experiences on his first day, “Rearden was the opposite of the rez. It was the opposite of my family. It was the opposite of me. I didn’t deserve to be there. I knew it; all those kids knew it. Indians don’t deserve shit.”32 He even graphically details the differences in dress of “Indian” and “White” students.33

34

34

Alexie’s work ultimately reveals that American Indian students who leave the reservation in search of greater educational opportunities face the need to code-switch to the dominant culture in order to fit in.

This focus on code-switching to mainstream culture as a means to a successful future is also apparent in the current debate of whether or not African American English (AAE) should be an acceptable form of communication in school. AAE is influenced by the pronunciation and grammar of several dialects and languages, such as Creole, Southern American English, and West African. The students in my school are primarily African American and use AAE when talking with family members, friends, and within their community. When they arrive at school, they are asked to code-switch to Mainstream American English (MAE) as the “proper” way to approach their academics.

In the book Ebonics: The Urban Education Debate, the authors argue that, “Unfortunately, language diversity, like ethnicity, social class, religious affiliation, and so-called racial diversity… provide a means for differences among us. These differences then provide a means for positioning people as being either superior or inferior.”35 Instead of embracing the differences between us and honoring them in the classroom, schools reinforce the message that only the dominant culture is necessary.

Similar to the anecdote of Luther Standing Bear being forced to choose an American first name, my students often see their names misspelled on grade printouts as the computer system does not accommodate non-white spellings of their names. For example, a student may spell her name Elle’anna, but the computer prints it as “Elleanna,” an MAE version of her name. She would often pull out a pen and angrily place the apostrophe in its appropriate place on the print out. Even though this may seem like a small cultural slight, when added up, these cultural slights send the message of, “your culture is not accepted here.”

In recent years, attempts have been made to bring attention to the rich diversity of student culture and its importance in the context of education through the bidialectalism movement.36 The philosophy of bidialectalism is to value student culture and actively provide students with opportunities to use their native culture in the classroom along with mainstream cultural practices and expectations. The proponents of this movement believe that by valuing student culture, the systemic eradication of student culture in classrooms can be reversed.

Encouragement of cultural differences also provides novel perspectives. The Blackfeet Tribe of Montana has founded three schools for language and cultural immersion of their youth. As part of this immersion, students are taught the Blackfeet language, which does not have gender distinctions.37 Imagine how differently these students see the world through the context of their culture. To remove this perspective is to homogenize the human experience.

The pressure on today’s students to conform to mainstream culture through code-switching is eerily reminiscent of the conversion of American Indians to Christianity and civilization through education. Mainstream society is trying to “civilize” our students by requiring them to code-switch and only express themselves through mainstream culture. Students are once again being assimilated and their culture eradicated. We live in a world of diversity where countries and cultures are no longer isolated from each other as they once were. It is time that we celebrate and welcome these differences in the classroom.

Comments: