Unit Concepts

The progression of concepts addressed in this unit is as follows:

Concept #1: Adding and Subtracting in the Context of Length Measurement

Concept #2: Adding and Subtracting Integers as Vectors

Concept #3: Adding and Subtracting Fractions with Like Denominators

Concept #4: Adding and Subtracting Fractions with Unlike Denominators

Concept #1: Adding and Subtracting in the Context of Length Measurement

Addition

In my experience, by middle school, students are well aware of the elementary principle that addition, at least of whole numbers, can be seen as the act of putting things together. To ensure that all students have a firm grasp and are able to articulate this concept in the most general sense, I will start this unit by using arbitrary bars of various lengths length in the absence of units and number. Students generally have little experience with this type of model. Usually students rely on sets of tally marks or counting objects to show addition in the context of whole number addition. Students will count one set of objects and the count on to the second set to find the total. Consequentially, this limited experience causes some students to narrowly see addition as the act of counting on. This device falls short when students are then asked to add non-whole numbers, as it is difficult to represent and count on with fractions and decimals. Instead, the discussion of addition using length of bars rather than sets of objects allows us to make the more general and transferrable point that no matter what quantities we are using, fraction or whole number, addition is a matter of putting quantities together. Also the use of bars is purposeful in that it allows students to make an easier jump to seeing numbers in terms of linear measurement on the number line. See the Figure 2.

Figure 2

To find the sum of bar a and bar b we simply put them together and take the total length. This geometric representation forces students to view addition as: the “putting together” of things instead of just a symbol that signals us to count on. (Howe 2016)

Commutative Property

At this point in the progression it will be useful to show the commutative property of addition. See Figure 3.

Figure 3

Figure 3 invites students to grapple with the fact that it does not matter which order bar a is put together with bar b, they will always equal the same thing, thus making a geometric argument for the commutative property. This simple illustration will be useful for the entire year of study because they provide an agreeable and clear way of viewing this property, making it easier to draw upon when we need it again in topics like algebra.

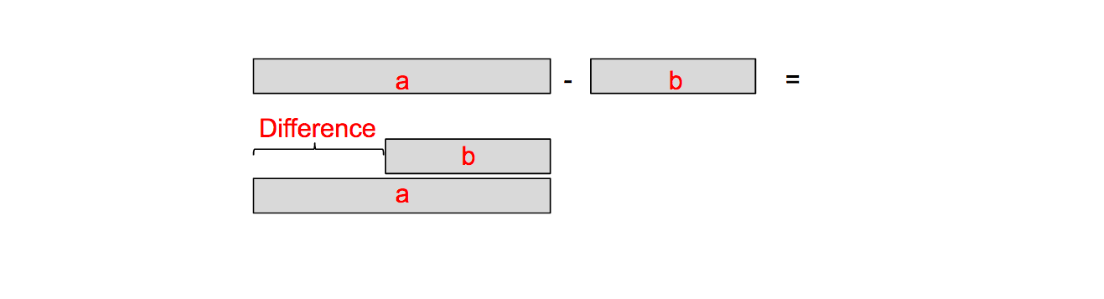

Subtraction

Students often hold a narrow view of subtraction as only the act of “taking away”. Students must also see that subtraction has a lot to do with comparing. To solidify this understanding in the absence of numbers, I will show them subtraction in terms of lining two bars up and comparing the lengths. See figure 4 below.

Figure 4

If we compare bar a with bar b, we can easily see the difference as the overhanging piece represented. Students must be aware that the bars are to be stacked so that they are evenly lined up at one end to make an accurate comparison. This condition needs to be firmly established, because it will be used again when we advance to seeing the subtraction of numbers on a number line.

I do not expect to spend more than two or three class sessions solidifying these concepts. My experience leads me to believe that this will mostly be intuitive and easy to grasp for a middle school audience. Although seemingly basic, these ideas will be used as a basis for reasoning and a way of thinking about addition and subtraction that is symbol independent. This idea of putting together and comparing will be the common language used throughout this unit. It is important to note that some students will have a very narrow and ingrained view of addition and subtraction. Students rely on counting and taking away strategies, which are no longer useful once they are required to operate with different denominators, decimals, or signed numbers.

When students demonstrate an understanding of this “putting together” and “comparing the difference” of bars, I will then task them with this same reasoning but on the number line, giving these bars a numerical value in terms of length. Finally I will transition the bar representation of numbers to vector representations, preparing them for the next concept.

Concept # 2: Adding and Subtracting Integers as Vectors

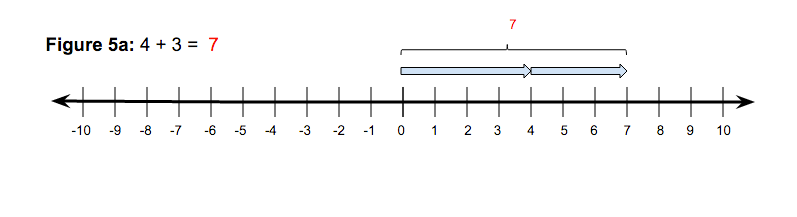

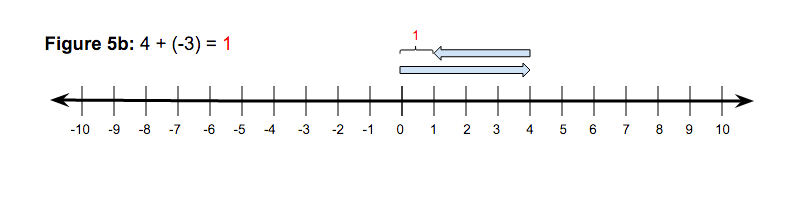

Adding Integers

Established in the prerequisite unit, Rational Number Placement on the Number Line, and again in Concept 1 of this unit, students will already have an understanding of representing positive and negative numbers as magnitudes of distance with an orientation. Students should then make the connection that adding and subtracting positive and negative numbers is just a matter of putting together and comparing these numbers on a number line in relation to the origin. Consider Figure 5 for an example of both adding two numbers with the same sign and adding two numbers with different signs.

Figure 5

I find that it is essential to use careful and consistent language in discussing these vector representations. For Figure 5a, we move 4 units in the positive direction to the right so we place a vector starting at the origin and extend it to 4 in the positive direction. The plus sign signals the putting together of the following number in its original orientation which is again in the positive direction since it is a positive 3. Now we can see that the combined distance, stretching from the origin to the endpoint of the second vector is 7. The language of movement is key here. For example, “We move 4 in the positive direction and then 3 more in the positive direction.” This explanation gives further justification for the vector representations. In Figure 5b the vector positive 4 is put together with a negative 3 which students will know as a vector length of 3 units directed to the left. Because we are adding, we put them together by starting the vector at the end of the 4. This vector is stacked above the first one, which affords us to see both vectors separately. The distance from the endpoint of the second vector to the origin, 1, is then the sum. These basic examples of addition and subtraction are where precise language needs to be pinned down. Students should be able to easily agree with these representations and the accompanying explanation. Students will exercise this idea with multiple examples in order to adopt this new way of thinking. This will finally provide a sound frame of reference when operating with positive and negative numbers in the abstract, which traditionally for my students is a point of struggle.

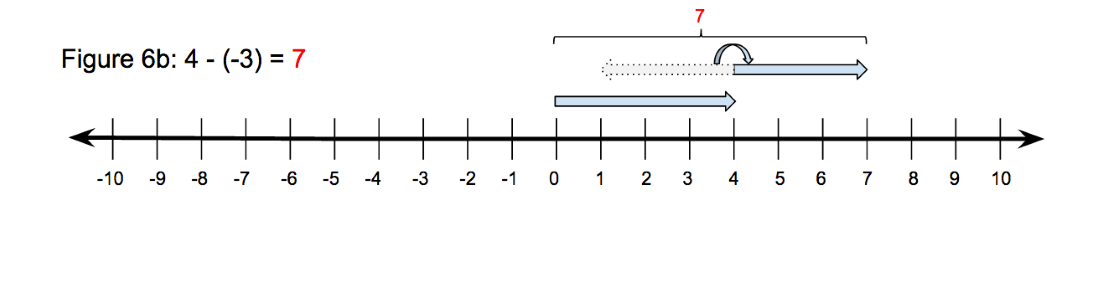

Subtracting Integers

When moving to subtracting integers, students should use the same logic we used when subtracting bars. We line them up and then compare. Then to build from this logic, we need to use some additional language to explain what is happening in relation to the number line.

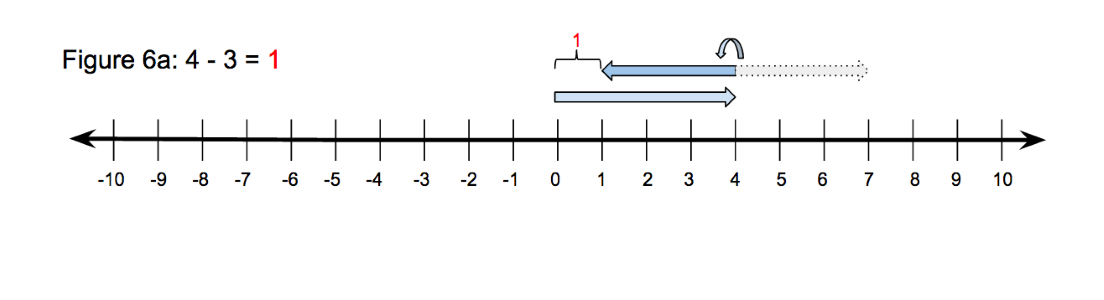

Figure 6

In Figure 6a, we bring 4 minus 3 to the number line. A positive vector starting at the origin represents 4 and a vector with a length of 3 is combined only this time with subtraction. Before the 3 is combined, we change its orientation since we are subtracting it. Subtraction amounts to addition of the negative. Now we compare the endpoint of the second vector to the origin for the remaining distance, which is the difference. After enough experience with seeing subtraction as changing the orientation of the second number before adding, students should realize that this is the same action as adding the opposite number, seen in Figure 5a. This is the key takeaway of this lesson.

Subtracting a negative number as seen in Figure 6b follows this same logic. -3 is seen as a vector directed to the left, but then, we change the orientation to the opposite direction since we are subtracting it. After flipping the -3 to a +3, we add it to the +4 in the familiar way. The distance of the end point of the second vector to the origin is then the difference, 7. Again the point here is to not rely on other devices for understanding this. The subtraction sign should be viewed as flipping the orientation or the ensuing number. If students are relying on an understanding where subtracting is simply taking away, it becomes difficult to conceptualize the taking away of a negative quantity. The point needs to be made that subtraction does not necessarily mean “go left on the number line”, rather it signals us to take the opposite of the subtrahend and then add. If it is viewed this way, we can make a stronger connection of addition to subtraction. Good! Students will ultimately reach the conclusion that subtraction is just addition of the additive inverse, and in this sense, subtraction is absorbed into addition.

Subtracting signed integers, in my experience is a complicated concept for students to grasp and becomes more so when signed fractions are involved. It will be important that students see many examples of the different variations of subtracting integers: subtracting a positive from a positive, positive from a negative, negative from a negative, and negative from a positive. Students should be able to see the same task happening and unify their understanding of subtracting integers no matter what combination they are presented with. Further, the goal is that students understand that just as adding and subtracting positive numbers extends uniformly to adding and subtracting positive rationals, adding and subtracting integers extends uniformly to adding and subtracting all signed rationals.

Concept #3: Adding and Subtracting Fractions with Like Denominators

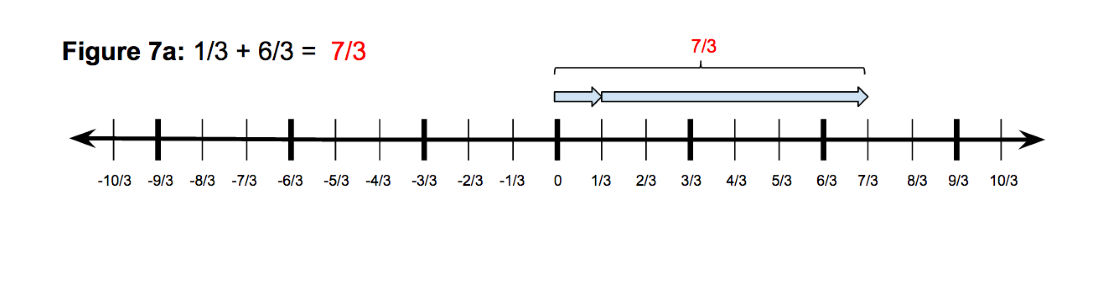

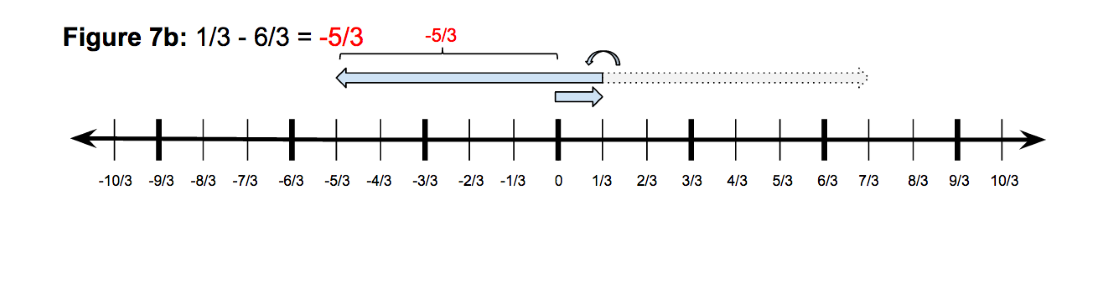

In the prerequisite unit, students will have mastered representing all rational numbers. In concepts 1 and 2 of this unit we have established the essential understandings of adding and subtracting integers on a number line. Therefore adding and subtracting fractions with like denominators should be a matter of calling on these same understandings. It is the same thing, but with a smaller unit. Here it is essential that students make the connection that what we do when we operate with fractions is the same as what we do when we operate with integers. It is a matter of putting quantities together. See Figure 7a and 7b for examples of addition and subtraction.

Figure 7

Concept #4: Adding and Subtracting Fractions with Unlike Denominators

At this point in the unit we will address the challenging concept of adding and subtracting fractions. The number line is an excellent place to deal with this concept, because it exhibits the need to find a uniform unit. Finding the sum or difference then becomes a matter of subdividing the unit in a way where the intervals express a common denominator. The issue of renaming, or what is usually called making equivalent fractions, requires separate consideration before moving on to adding and subtracting so that students do not blindly depend on methods that allow them to simply find common denominators and then operate.

Renaming Fractions

The essential understanding to reach regarding renaming fractions is that it is a matter of renaming a quantity, by expressing it in terms of a different unit. Students often demonstrate a deficient understanding of equivalent fractions, because of their incomplete understanding of the abstract concept of equivalency. (Hung-Hsi Wu 2013) When discussing this concept as renaming it is making the obvious and correct implication that the quantity of the fraction remains unchanged and we are just giving it a new name by using different terms. Students are generally familiar with the method of creating equivalent fractions by multiplying the numerator and denominator by the same factor. However this procedure is often done in the absence of reasoning that the physical quantity remains the same. Renaming fractions on the number line allows students to create equivalent fractions while still reasoning about quantity. Just as in the prerequisite unit, where student understanding of fractions was shepherded from area models to the number line, we must guide the renaming of fractions in the same way.

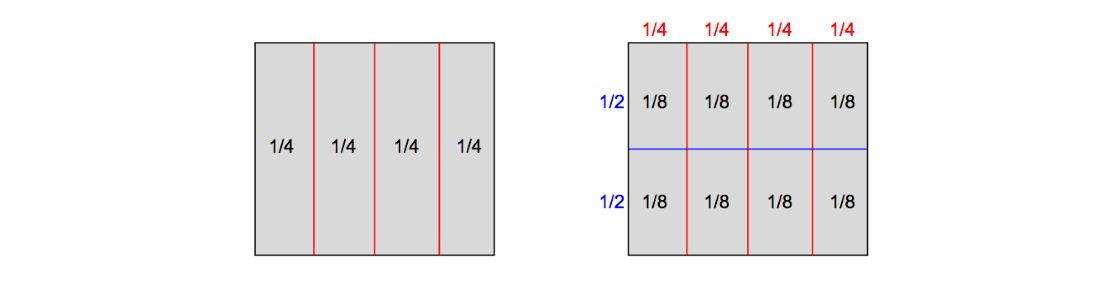

First we need to develop the idea of what it means to be the same, because for many students this is not obvious. To do this we can start with area model representation of fraction in terms of a unit rectangle. See Figure 8. Vertical lines to show fourths first divide the rectangle. When referring to each piece, it is important to use the language that was established in the first unit. Each piece represents 1 of something that takes 4 of to make a whole. (Gross 2012)

To rename this fraction in different terms we can introduce the term “subdivision”. As seen in figure 8, the horizontal line shows that the unit was divided into half, thus subdividing each fourth piece into two equal parts. Students will be able to now see that the unit is divided into 8 equal pieces. They are eighths of the whole. Finally I will draw students to attend to the 1/4 pieces and bring them to the realization that we can rename them in terms of eighths. It is then visually justified that 1/4 is the same as 2/8. Although basic, this illustration is important in framing the discussion of renaming fractions as the task of expressing the same quantity in different terms.

Figure 8

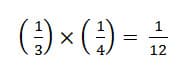

Once students are thoroughly comfortable with the above example of subdividing area models, I will help my students see how renaming fractions works on a number line. See Figure 9. This area model demonstrates the same logic as in Figure 8 by starting with an initial unit divided into thirds and then subdividing each piece into fourths, creating twelfths. Again, it is important to emphasize that all the thirds of fourths are equal. So, since 12 of them make the whole (the unit interval), they are twelfths. We can also conclude that:

This representation in Figure 9 is one with which students do not have much experience, but it is an important step towards helping them see equivalent fractions on a number line. When we subdivided by using parallel lines we essentially divided the unit by length, which is the same task as dividing a unit interval on a line. We can then shrink these area representations down to the number line, preserving the connection of renaming the fraction of an area and renaming fraction of length on a line.

Figure 9

After we have established the idea of subdivision to rename fractions in different terms and carefully shepherded this idea to a line, we can apply this logic on the number line. Instead of subdividing areas, on the number line, we are tasked with subdividing each length interval. See Figure 10. Here 1/3 can be subdivided into each 2 equal parts to make intervals with a length of 1/6. If instead, we subdivide an interval of length 1/3 into 3 equal parts, we will make lengths of 1/9, and so forth.

Figure 10

As with the area models, the number line affords us with an agreeable illustration of fractions with different names that represent the same quantity. With enough experience renaming fractions in this way, students will notice that by subdividing any given interval by any number, d, you are multiplying the original number of intervals by that number, d, making the new denominator. By highlighting the equivalent fractions, we can generalize to the following statement, which we will call the “Renaming Principle”:

For any fraction, a/b = ad/bd, for any whole number d.

Finding Common Denominators

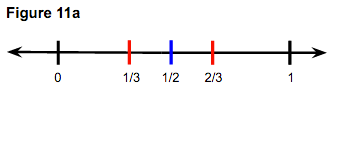

After students have a firm grasp of seeing and creating equivalent fractions on a number line we will deal with the issue of fractions with different denominators, so that eventually we can add and subtract with them. I will start by creating a need for a common denominator by presenting students with a number line model like figure 11a. Here we can see both 1/3 and 1/2 on the same line creating intervals of different lengths. Students should see uniformity and symmetry with the intervals and will be prompted as part of a number talk to try to find the lengths of these undefined intervals. After having them grapple with this issue, we can eventually arrive at the notion that in order to find these distances we need to find common denominators by renaming.

Figure 11

It will be helpful to address this concept with two number lines with the different fractions represented on each. See Figure 11b. By subdividing the intervals of the 1/3 intervals by the denominator of 1/2, we will arrive at a common denominator of 6. Here we can see that 3/6 lines up perfectly with 1/2, therefore 1/2 can be renamed as 3/6. This can also be done by subdividing the 1/2 intervals by 3. Because a given fraction can be renamed to have a denominator of any multiple of the original denominator, two fractions can be renamed to have a common denominator. In particular the common denominator can be the product of the two original denominators. The principle is defined more concisely as:

Given any 2 fractions a/b + b/d both can be renamed as fractions with the same denominator. In particular: a/b=ad/bd and c/d=bc/bd.

So that students become more familiar with this idea, they will engage in multiple tasks where they will be required to find common denominators for fractions with different numbers.

The main point here is that by renaming fractions with different denominators, there will always be a common denominator. This varies from a more typical treatment of common denominators by not pushing students to find the least common denominator. In my experience, students often latch on to the idea that a least common denominator needs to be found in order to do anything with different denominators. This effort takes the focus away from the main point of simply finding a common denominator. The least common denominator is a refinement that can be reached once students completely understand the concept and benefit of renaming fractions in like terms.

It is my expectation that asking students to add and subtract fractions with unlike denominators will be an easy next step to take. This is only because we have progressed so carefully through a progression of understandings that get students to realize the process of finding common denominators while always thinking about quantity in terms of the number line. It is my hope that students will ultimately utilize the concepts and skills addressed throughout the entire unit to do this task. They will have first to find a common denominator by renaming each fraction by subdividing the intervals on the number line so they can properly place both vector lengths on the same number line and then follow the already known routine for adding and subtracting fractions with the same denominator. Although tedious, part of the point of doing this on the number line is that it will ground their conceptual understanding of this process with a sound representation so that they can better reason about computing fractions abstractly. It should help them see that it really is the same process as in adding whole numbers. The difference is only in the symbolic representation.

Comments: