Content Objectives

My goal is to teach fractions using the number line and the Navajo loom and rug. The loom and rug are mediums to math, and to Diné culture and language. The enduring understanding of learning the processes of fraction when creating or using a medium is what students will be able to apply into other content or another grade level. The objectives of my curriculum is to add and subtract fractions, equivalent fractions, multiply and divide fractions, convert measurement units (a small rug to a larger rug), while using the number line, so students have a solid understanding of fractions when given different forms of fraction.

Add and Subtract Fractions and the number line

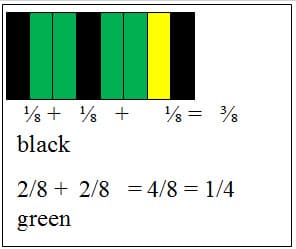

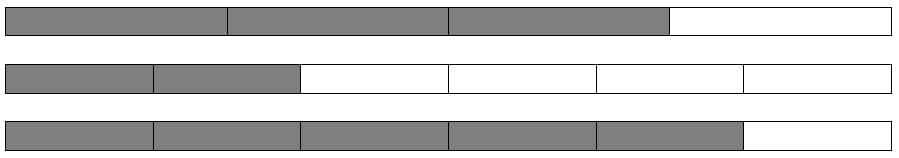

Like fractions are fractions with common denominator and you are able to add and subtract the numerator then rewrite the same denominator. Then the thinking part is working with fractions with unlike denominators. When working with unlike dominators, the least common denominator is attained when multiplying the number and the denominator by the same factor to make an equivalent fraction. The diagrams below are examples of unlike fraction using area model and a number to model how fractions are equivalent. Students will use this method when using Navajo rugs with stripes.

Area model of addition

Question: If ⅜ of a rug consists of black stripes, and 2/4 of the rug consists of green stripes, what fraction of the rug is either black or green?

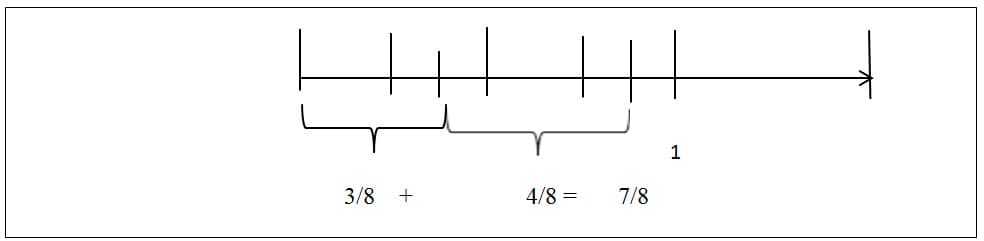

3/8+4/8=7/8

Linear Model

Solution

Convert Measurement Units

There is a lot of technology programs used to scale objects. My students will learn how to scale components of a small rug into a larger rug. They will look at size, which tells something about an object’s dimensions in relation to other things. Most cultures have an established system of measurement to have a clear dimension of objects. The height of a horse is so many hands high, this make a mental comparison for the given object and the measurement. Once the object is measured, we can scale the size. Scale means size in relation to some unit of measurement that is larger or smaller. For example, when drawing a ¼ scale and I want to change the scale so ¼ inch equals 1 foot, then we are relating two sets of measurements. The challenge is moving between scales to understand the difference between the scaling of something in “linear measurements” versus “area measurements.”6 We would only need the dimensions of the original small rug and to scale up to a larger frame as a surface measurement. This refers to proportion to the ratio between the parts of the small rug as a whole surface. The grid is a system of fixed horizontal and vertical divisions.7 Anything, no matter how complicated or irregularly shaped, can be conceived of in terms of X (horizontal) and Y (vertical) axes.8 When changing the scaling size the X and Y coordinates need to be measured in appropriate proportions. The grid is a compatible tool students will use to scale up the small rug into a larger frame. Students will practice scaling as math measurement tool. It represents a real world problem solving strategy and a mathematical problem by graphing points to the coordinate plane, and interprets coordinate values of points in the context of their situation. It is a challenging activity, requiring analysis and hands on manipulation.

Approach to fractions

We will start our study of fractions with unit fractions. We will use basic fraction measurements which are ½, 1/3, ¼, 1/5, and so forth. For example, ½ of a whole is something it takes 2 of to make the whole. Since two pints is equivalent to a quart, a pint is ½ of a quart. Similarly, 1/3 of a whole is something that it takes 3 of to make the whole. So 4 inches is 1/3 of a foot, because 3 lengths of 4 inches make 12 inches, which is a foot. This is an example of a length model for fractions.

|

12 inches = 1 foot |

||

|

4 inches |

4 inches |

4 inches |

|

1/3 foot |

1/3 foot |

1/3 foot |

Likewise, ¼ of a whole is something that it takes 4 equivalent parts to make a whole. So when we cut a square into halves both horizontally and vertically, then each of the small squares is ¼ of the whole square, since 4 of them fit together to make the whole square. This is an example of an area model of fractions. Another example is, one day is 1/7 of a week, because there are 7 days in a week and one hour is 1/24 of a day, because there are 24 hours in a day.

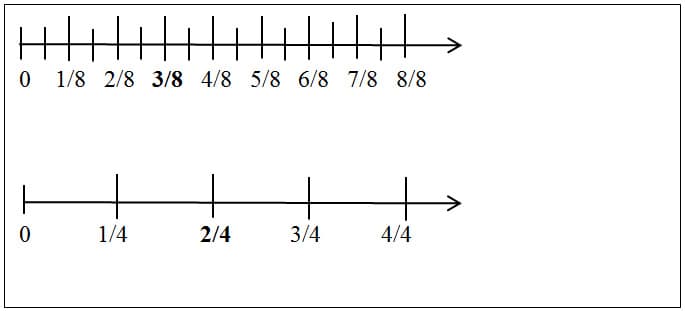

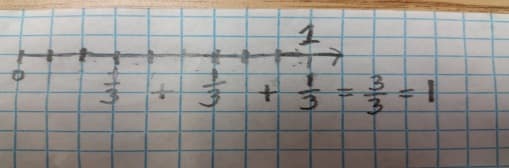

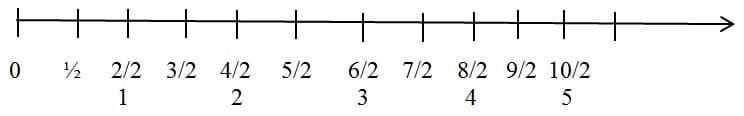

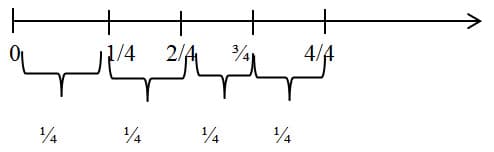

On the number line, unit fractions are given by distances that are part way from the origin to 1. So ½ marks the mid-point on the unit interval, since we begin from 0 to the midpoint, and measure ½ again, we will get to 1. Similarly, ⅓ is the leftmost of two points that divide the unit interval into 3 equal parts, since we begin from 0 to the point of ⅓, and ⅓ again, and ⅓ again, 3 times in all, we will get to 1.

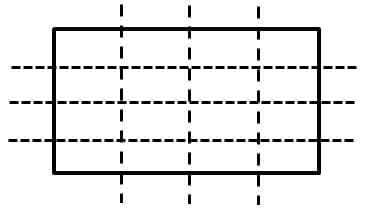

We learned the easiest way to represent fractions is by area models. For an area model, we will use a rectangle to represent the whole. Then we can find 1/d of the rectangle by cutting the rectangle into d equal strips, either horizontal or vertical. Any one of the strips is equal to 1/d of the whole rectangle. If we use vertical strips, and take the base of the rectangle to be the unit length on a number line, then the area model can be thought of as a thickened version of the number line model. This is a very valuable connection between the two models, and can be used to transfer interpretations from one model to the other.

When discussing unit fractions, I will make sure that my students learn and know the fact, that for unit fractions of a fixed unit, the larger the denominator is, the smaller the unit fraction is. Then,

1/2 > 1/3 > 1/4 > 1/5 > 1/6

and so on, and forever. This is simple to see using either the area model or the linear model. Also, it makes sense: since two copies of ½ makes the whole, but two copies of 1/3 only makes 2/3, which is less than the whole, 1/3 must be less than ½.

Figure 1. 1/3 < 1/2

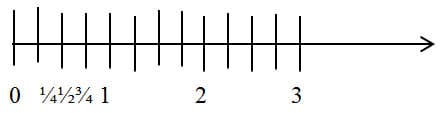

Once my students have a solid base with unit fractions, I will introduce general fractions as multiple copies of unit fractions. For example, 2/3 is 2 equivalent copies of 1/3, and ¾ is 3 equivalent copies of ¼, and so on. This is when fraction strip tiles are used so students are able to demonstrate the equivalent fraction examples.

In the area model, a general fraction can be represented by subdividing the rectangle into equal strips, with the number of strips equal to the denominator of the fraction, and then shading the number of strips specified by the numerator. The strips can be either horizontal or vertical. Here are examples of area models for the horizontal fractions ¾, 2/6, and 5/6.

The number line is an excellent way to represent all the multiples of a given unit fraction. After 1/d is placed on the number line, 2/d is at twice the distance from the origin as 1/d, and 3/d is at 3 times the distance, and so forth. This makes it very easy to show all the multiples of 1/d. It is a good model for making the point that fractions can be larger than 1. It also presents an attractive geometric picture: the multiples of a unit fraction give a subdivision of the number line that looks just like the subdivision given by whole numbers, except that it is finer. There are d intervals of length 1/d in each unit interval. The figures below show the multiples of ½ and of 1/3.

After students get an idea of what the multiples of a given unit fraction look like, we will discuss adding fractions with the same denominator, and multiplying a fraction by a whole number. The length model is excellent for studying these processes. Adding always corresponds to putting lengths end to end, and multiplying a length by a whole number corresponds to taking that number of the same length, and putting them all end to end.

By making strips equal to the lengths of the given fractions and putting them together end to end, I believe that my students will be able to see that the sum of two fractions with the same denominator is the fraction with the same denominator also, and with numerator equal to the sum of the two given numerators. For example,

3/2 + 5/2 = 8/2, and 1/3 + 4/3 = 5/3

It is nice to put bars representing the two fractions along the number line, and see that the addition is just like whole number addition, but with a smaller unit. The two additions just mentioned are illustrated below.

After extensive independent practices of general fractions as quantities, I want my students also to understand that a fraction can be thought of as the result of division, even though it is not defined that way. For example, although ¼ is defined as equal to what you get by dividing the unit into 4 equal pieces, ¾ is defined as 3 copies of ¼, not as what you get by dividing 3 into 4 equal pieces. However, the number line gives a good way to show that these two things are equal. This can be seen in figure below.

The interval from 0 to 3 is subdivided into 12 intervals of length 1/4, and then we can make 4 pieces consisting of 3 intervals of length ¼. Each of the 4 pieces has length ¾, and together they make the interval of length 3, so ¾ is ¼ of 3. That is, ¾ is 3 divided by 4. I will ask my students to give a similar explanation of some of other examples, such as 2/3 is 2 divided by 3, and 5/6 is 5 divided by 6.

We will also talk about comparing two fractions with the same denominator. This is very easy: the fraction with the larger numerator is larger. This can be easily seen by using both the area model and the number line model, although the number line model may be easier to use with fractions larger than 1.

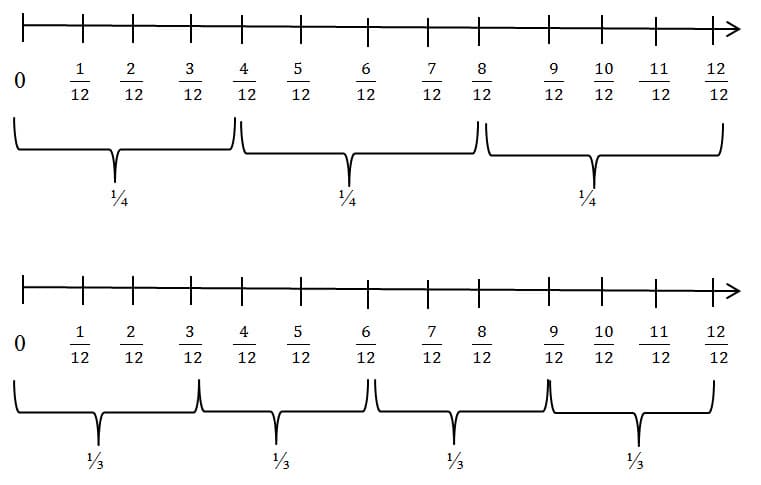

When my students seem comfortable with fractions as quantities, and with the arithmetic of fractions with a fixed denominator, I will introduce the idea of renaming: that a given number can be represented by fractions with different denominators. This is also called fraction equivalence. I will use both area models and linear models to show this idea. Using a rectangle to represent the whole, we can divide it into 3 equal horizontal strips, and then we can also subdivide it into 4 equal vertical strips. The result will be that the whole is subdivided into 12 equal small rectangles. So each small rectangle represents 1/12 of the whole. But also, each horizontal strip, which is 1/3 of the whole, consists of 4 small rectangles, so it is also 4/12 of the whole. This means that 1/3 = 4/12. Looking at the vertical strips, we can reason in the same way to conclude that ¼ = 3/12. This means that both 1/3 and ¼ can be thought of as multiples of 1/12: 1/3 = 4/12, and ¼ = 3/12.

The renaming process can also be modeled on the number line. To do this in the case of ¼ and 1/3, subdivide the unit interval into 12 = 4×3 equal subintervals. Each of these has length 1/12. If we group the 1/12s into consecutive groups of 3, we get 4 equal pieces that fill up the unit interval, so 3/12 = ¼. If we form consecutive groups of 4 small subintervals, we will get 3 equal pieces that fill up the unit interval, so 4/12 = 1/3. This is the same example we gave earlier, when we said that 4 inches = 1/3 foot.

I will have my students look at many examples of this process, using both area models and linear models, until they are confident about two important conclusions:

i) Any fraction can be renamed to another fraction by multiplying both the numerator and the denominator by the same whole number. The renamed fraction represents the same number.

ii) Given two fractions, both can be renamed to fractions with the same denominator, which is the product of the two original denominators.

These facts make it easy to add fractions, to subtract fractions, and to compare fractions. Given two fractions, to add them, just rename both to have the same denominator, and then add the numerators. For example,

2/3+ 1/4 = 8/12 + 3/12 = 11/12

2/3 + 1/4 = (2x4)/(3x4) + (1x3)/(4x3) = 8/12 + 3/12 = 11/12.

The same strategy can be used to subtract fractions. As an example, here is a word problem related to Navajo rugs.

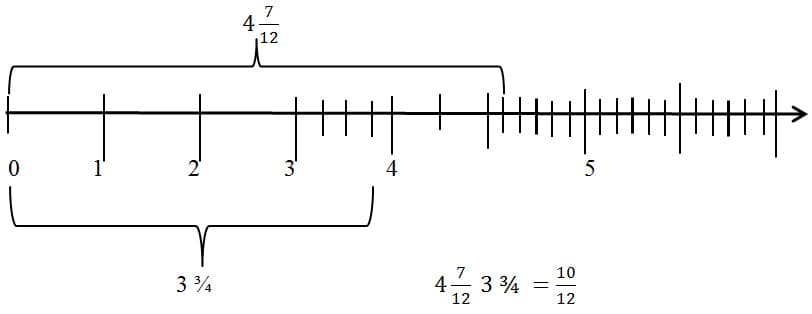

The Ganado pattern rug is 4 7/12 feet tall. The Two-Grey Hill rug is 3 ¾ feet tall. How much taller is the Ganado pattern then the Two Grey Hill?

We must find the difference 4 7/12 – 3 ¾. First, we can subtract the whole number parts: 4 – 3 = 1. So 4 7/12 – 3 ¾ = 1 7/12 – ¾. To subtract the ¾, we should find a common denominator for both fractions. We could use the method above, and take the product of the denominators. This would give us

1 (7×4)/(12×4) – (3×12)/(4×12) = 1 28/48 – 36/48.

2

To complete the calculation, we need to convert the 1 into 48/48. Then we get

1 28/48 – 36/48 = 48/48 + 28/48 – 36/48 = (48 + 28 -36)/48 = (76 – 36)/48 = 40/48.

Although the product of the denominators always gives a common denominator for two fractions, sometimes we can find a smaller common denominator. In this problem, it would be simpler if we use what we discussed above, that ¼ is equal to 3/12. Then we could calculate

1 7/12 – ¾ = 1 7/12 – 9/12 = 12/12 + 7/12 – 9/12 = (12 + 7 – 9)/12 = 10/12.

Since 10/12 = (10×4)/(12×4) = 40/48, the two answers we got are equivalent.

Still another way to solve this problem is to convert all the measurements into inches. Since 1 inch = 1/12 feet, we see that

4 7/12 feet = 4 feet, 7 inches, and 1 ¾ feet = 3 9/12 feet = 3 feet, 9 inches

So

1 7/12 feet – 3 ¾ feet = 4 feet, 7 inches – 3 feet, 9 inches = 1 foot, 7 inches – 9 inches = (12 inches + 7 inches) – 9 inches = 19 inches – 9 inches = 10 inches = 10/12 feet.

I will have my students solve problems like this in several different ways to help them see how the different strategies are connected.

To compare two fractions, rename them to have the same denominator, and then compare the numerators. For example, take 5/6 and 7/9. Rename

5/6=(5×9)/(6×9)=45/54,and 7/9=(7×6)/(9×6)=42/54

Then since 45 > 42, we know that 5/6 > 7/9. This can also be seen by representing both fractions on the same number line, and comparing the lengths.

After my students are comfortable with the renaming process and can add, subtract and compare fractions, I will have them study multiplication of fractions. The area model gives a good way to visualize this process. Here is the example of (2/3)×(2/5). Draw the rectangle representing the whole, and subdivide it into 5 equal horizontal strips, so that 2 of these strips is 2/5 of the whole. Then also subdivide the unit rectangle into 3 equal vertical strips. Each horizontal strip is also subdivided into 3 equal small rectangles. There are 15 of these small rectangles, so each one is 1/15 of the whole. Also, If we take the intersection of 2 vertical strips with the 2 horizontal strips making 2/5, we get 2/3 of these 2 strips, so we have 2/3 of 2/5, which is what we mean by (2/3)×(2/5). But we can also see that this region consists of 4 of the small rectangles. The conclusion is that

(2/3)×(2/5) = 4/15. I will have my students do examples of this process, until they can explain the general rule:

iii) To multiply two fractions, multiply their numerators, and multiply their denominators.

Simplifying fractions

The example above, of the Ganado and Two Grey Hill rugs, shows that sometimes, when computing with fractions, you will end up with a larger denominator than you need. It is nice to have a denominator as small as possible, because fractions with small denominators are usually easier to interpret. For example, it is easier to think about ¾ than 51/68, although they represent the same number. For this reason, it is nice to know how to simplify a fraction, which means: rename it to a fraction with a smaller denominator.

Simplification is just fraction equivalence in reverse. Since we can check that

(3x17)/(4x17) = 51/68, we know that they represent the same number. But if we are just given 51/68, how can we know that it simplifies to ¾? The answer is that 17 is a common factor of 51 and 68: it divides both of them. Once we know that 17 divides both 51 and 68, we can divide to find 51 = 3x17 and 68 = 4x17, and then the rule for fraction equivalence, read in reverse, says that 51/68 = ¾. So to see if a fraction can be simplified, we should look for common divisors of the numerator and denominator. There is a systematic way to do this, but if the numerator and denominator are not too big, maybe the simplest approach is just to factor both of them into prime factors, and to see what factors they have in common. They can be divided by any common factor, and the resulting quotients will be the numerator and denominator of a fraction that expresses the same number as the original fraction.9

Here are some examples:

36/54 = (2x18)/(3x18) = 2/3. 12/20 = (3x4)/(5x4) = 3/5.

54/60 = (9x6)/(10x6) = 9/10. 35/42 = (5x7)/(6x7) = 5/6.

The rule to remember here is another version of the renaming rule.

Simplifying Fractions:

when the numerator and denominator of a fraction have a common factor,

both the numerator and denominator can be divided by the factor,

without changing the value of the fraction.

Renaming and simplifying fractions helps with planning rugs. Suppose that a rug has 80 weft threads. Then a stripe of one color made from 10 weft threads is 10/80 of the whole rug. We sense it is easy to see that 10 divides both the numerator and denominator, we see that we can simplify 10/80 = 1/8. So we can plan to make 8 stripes of with a width of 10 weft threads. Renaming can also help the in the other direction. Suppose we want to make a stripe that is 2/5 of the length of the rug. Since 80 = 16x5, we can rename

2/5 = (2x16)/(5x16) = 32/80. This means that our stripe should be made of 32 weft threads.10

Comments: