Measurement misconceptions

In my unit, I will address student misconceptions for the understanding of an area and volume of rectangular arrays.

The deception of adding and multiplying unit squares can be a big misconception to students. When my math students are solving measurement activities in the classroom, one of the biggest misinterpretations they have concerns the appropriate uses of the operations of addition and multiplication.

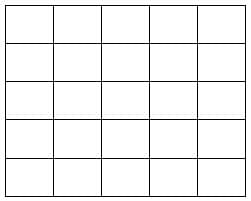

Customarily when students are determining an area of a particular array, they assume the area will be greater than the perimeter because multiplying rather than adding gives you a greater amount, (see figure 2).

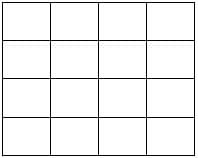

In some arrays, perimeter will be greater than an area (see figure 3). More importantly, students need to understand that it does not make sense to compare length and area, because they are measured in very different units: inches versus square inches, or feet versus square feet, etc. Also, the numbers involved depend heavily on which units are used. For example, a square with side length of 2 feet will have a perimeter of 8 feet, and an area of 4 square feet, or a perimeter of 96 inches, and an area of 576 square inches.

Figure 2 Finding the area of a rectangle, using an array and multiplication

(A= l ∙ w = 5 ∙ 4 = 20)

And the perimeter using addition

(P= S + S + S + S = 5 + 4 + 5 + 4 = 18)

Figure 3 An array with numerically greater perimeter than area (A= L ∙ W = 3 ∙ 3 = 9)

And the perimeter using addition (P= S + S + S + S = 3 + 3 + 3 + 3 = 12)

My students need to be careful only to add numbers that refer to the same unit. A common mistake is when a student tries to add centimeters and inches. “If there are three feet in a yard, then there are three square feet in a square yard. The mistaken conclusion is that two dimensional unit conversions are equivalent to linear unit conversions” (Carle).

For some students, the challenge is in spatial bias and equality assumptions. Students understand bigger is larger when interpreting arrays visually. When a student is comparing two rectangles, they will assume that the one that “looks bigger” of the two must have a greater area and perimeter because students have misunderstandings with spatial relations. The first rectangular array might be in the shape of a traditional square A = L ∙W = 3 ∙3 = 9 compared to one, which looks longer and stretched out but with the same area A = L ∙W = 1 ∙9 = 9. Because it looks stretched out, the second array will look smaller than the first one.

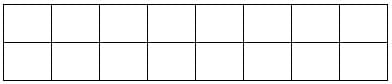

My students also struggle with the understanding that arrays with the same area also might have different perimeters. For example, if a (4 by 4) array (see figure 4) has an area of 16 square units, and a perimeter of 16 linear units, some students will assume an array with the same area will always have the same perimeter of 16. Students will be asked to determine the perimeter of a different array with the same area, an array of (2 by 8) with the same area of 16. The students will discover that the perimeter of this second array is 20 linear units, (see figure 5). “The number representing area must be greater than the number representing perimeter, since space is more, as a student once told me. The students fail to understand the importance and value of the units attached to the number,” (Carle).

Figure 4: Array of 4 ∙ 4 = 16 and P = 16

Figure 5: Array of 2 ∙ 8 with A = 16 and P = 20

Students continue to struggle with these misunderstandings because of their lack of strong foundation skills and lack of practice with the composing and decomposing of rectangular arrays. Some of my students look upon math as a thing detached from their everyday lives, lacking importance and value to better understand real life situations all of us face each day. In the real world, they continue stumbling through school accompanied by these misconceptions.

Comments: