Content

Mise en Scene

Mise en scene is a complex term compromised of four distinct formal elements.6

- Staging the action

- Physical setting and décor

- Manner in which these materials are all framed

- The manner in which they are photographed

As mentioned above, mise en scene is about setting the scene. The basic elements of mise en scene are composition, sets, props, actors, costumes, makeup, and lighting. Different sources show different specifics in terms of what is included, but it all comes down to what is seen and how it is seen by the viewer. All of these things are interrelated and equally important in the end, but for this unit, we will focus more on the aspects of framing the mise en scene, contextual framing, and territorial space. These connect to numbers 3 and 4 above.

The composition from frame to frame may change within a single scene as the camera pans in or out or from place to place focusing on different elements. Each scene may have its own feel or expression from the props and costuming employed. Diverse locations will give unique atmospheres and backdrops. Lighting can act to direct your attention or to change the time of day. How and when the elements of mise en scene are used changes everything about a film (or play, documentary, commercial, photograph, or painting).

Framing

In theatre there is a frame that goes over and around the stage, the frame is called the “proscenium arch”. It contains the action and set design on the stage, but includes all of the acting space used, even if it reaches out into the audience and beyond. In film that arch is the frame, both figurative and literal. The frame is a “masking device that isolates objects and people only temporarily.”7 The frame not only focuses on what the artist wants you to see, but how they want you to see it. We see framing in art all the time. It is important to pay attention to what is framed and how to gain an understanding of what the artist intended for us as a viewer to take in, understand, and relate to. It is no less important if it is a painting, a photograph, or a still from a movie. Alfred Hitchcock believed that in film an un-manipulated reality is filled with irrelevancies.8 He used the frame of the screen like a picture frame into which the audience is peering at what is going on and he was very intentional with every shot being an individual picture, like a painting. Despite its title, his 1954 film Rear Window is a master class illustrating this method and his skill in using the enclosing or centripetal frame. Comparatively, Francois Truffaut, a renowned French film critic, director, and producer, offers a window in which the eyes are often intentionally led off the screen. Centrifugally. His use of framing is quite different from Hitchcock’s, but both make exceptional use of the framing process. Regardless of which method is used, it should be intentional and well planned.

The use of the frame shows us what we should be looking at and where the action is, whereas on the theatre stage the spotlight does the better job of honing in on an actor to show you where to look within the proscenium arch. In photography you are generally shown one shot out of the many taken. The chosen photo will focus intentionally on certain things, people, or a scene, but that one moment in time is all you get in each photo. In film the camera will zoom in to where it wants you to focus from one scene to the next, there will be lighting or color that directs your attention, or there may be movement meant to catch the eye and direct you where to look. The director may be slow and intentional in a scene to get to the point of focus or they may be quick, perhaps with a blare of music or noise to direct your attention. Regardless of what is going on in the scene, setting, props, costumes, etc. the framing is going to dictate what the viewer sees and how they see it.

Contextual Framing

Cinematographer Robert Bresson said that, “Cinematographers film where the images, like words in a dictionary, have no power and value except through their position and relation”.9 Frame by frame, the movie comes together to form a sentence, a paragraph, and a story. It is important how the director frames each shot, like an author choosing the right words, in some cases more than others. Without the right framing the piece may get scrambled or misconstrued or completely loose the power it may have otherwise had. Private conversations held in a park at night give an entirely different viewpoint than a hushed conversation on the edges of a crowded party or shared during a slow dance on ballroom dancefloor. A shot may show the familiarity or foreignness of a situation or give hints to other things the viewer needs to know for a future part of the film. A director isn’t likely to zoom in on a handheld mirror at the end of a scene if that mirror holds no consequence whatsoever. The framing of the item would be out of context unless, of course, the director is trying to purposefully confuse, mislead, or vex the viewer.

Framing is the determination of what is actually in the single frame or shot and the angle from which it is shot. The director of a film has the important job of determining where the camera is, how much it is zoomed in or out, the angle of the shot, how focused items in the shot are, and so much more. One way to understand that is by looking at a single image with different framing that changes the context.

|

|

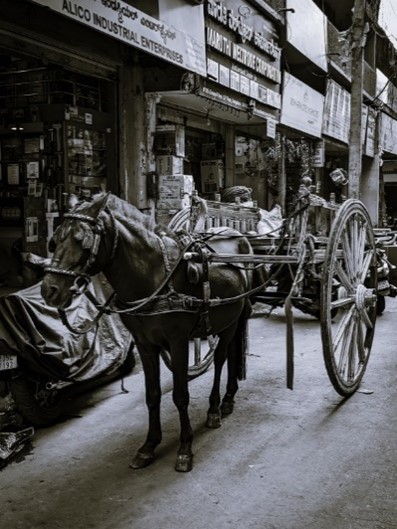

| Image 1. Horse and cart in the street.10 | Image 2. Horse in bridle. |

The importance of items in a scene can change greatly based on the framing of the image. In Image 1 we can understand the importance of the horse as it is pulling a cart in a market. It can be assumed that the driver has stepped into a store to buy or sell something. Compared to the cart, the horse looks a little feeble, perhaps, but capable. Image 2 focuses on only the horse. We may notice the harness or haircut of the horse, but where it is or what it is doing there is much less important than in Image 1. The horse in image 2 may seem a bit more sturdy and stout since we aren’t aware of what his body actually looks like. The framing changes the context. If the story is about a farmer taking his wares into the market, a close-up of the horse may be pointless, but if the story is about the horse, the close-up is evocative.

Territorial Space

The context of any shot is affected by the proxemics or range chosen by the filmmaker; this is the territorial space or the space between the viewer/camera and what is in focus on the screen. Territorial space is considered a comfort zone, or alternately, a un-comfort zone when needed for the film. Zooming in and zooming out can not only tell us what the main focus is but it can also be used to show the relationship between characters and things. Zooming in, or giving a close-up, can show the intimacy between two or more characters or the isolation of a single character. Zooming in can focus on a face, or faces, to note emotional states, intimidation, and confinement. Zooming out, or going for the long shot, can show the importance of the scene’s setting or what is going on in the scene, giving the viewer of bigger picture of the setting. Zooming out can also declare separation, alienation, or even freedom of the actors. There can also be extreme long shots and extreme close shots, full shots, and medium shots. The important thing is to relate the distance of the camera from the subject to what the director wants the viewer to feel or experience. Is it more important to show the horror on someone’s face or the horrible thing that is giving them such a reaction, or perhaps both at the same time?

Aspect Ratio

There are several characteristics to framing in film. One of these is the aspect ratio; that is the ratio of the frame’s horizontal and vertical dimensions. Some students may know about this from being able to use the TV remote control to change from standard to wide screen viewing. Sometimes a film may not fit the screen properly and we change the aspect ratio to fit our own screen. Interestingly enough, today’s regular (not widescreen) televisions use the same 1.33:1 screen ratio that movie screens in the 1930’s to 1950’s used. A widescreen TV typically has a 16:9 ratio. Today’s theater movies come in a standard ratio of 1.85:1 and a widescreen ratio of 2.35:1.11

This can become a problem for the intended framing when the screen doesn’t match the filmed aspect ratio. One of the activities for this unit deals with this and what has to be taken into account when making a student film regarding how it will be presented. Most students are used to making Tik Toks or Instagram videos with their cell phones, thus the image is up and down, the screen being vertical instead of horizontal. Therefore, when that phone screen is transferred over to the TV screen, you have the tall narrow image with black on both sides for most of the screen width. The same thing has to be dealt with involving movies that show on the big screen vs. the movies on the television at home. Do you have black lines on the top and bottom to view in widescreen or do you change the aspect ratio to be full screen, but lose part of the left and right sides of the original film? How important are those parts? We often see this as an issue when we want to print a picture. If the picture is too long, it may print onto a second page or end up with a lot of white space along one edge of the paper. We have to consider, what you are missing if you don’t have those edges on the screen when the aspect ratio to screen changes.

Composition and Design

Filmmakers and 2-dimensional artists alike must pay special attention to lighting, shape, color, line, and texture and both of these art forms typically use a flat rectangular surface. Within Classical Cinema, the artists use these elements as a balance or equilibrium, though some filmmakers (like some 2D artists) will intentionally break the balance to emphasize different aspects and to “present us with an image that’s psychologically more appropriate to the dramatic context” of a scene, image, or film.12 Since this unit focuses on realistic narrative, the scenery will not be fantastical, otherworldly, or imagined. The set will evoke and portray a real place, real people, and real situations. Therefore, the compositions will show this reality. That is not to say that the composition and design can’t be altered in the film, it is just that they won’t be going to very many extremes because compositional balance can be quite important when the purpose is realism. More often, light, shape, color, line, and texture will be used to draw attention to something specific that the filmmaker wants you to focus on, thus framing a shot to dictate what is important. Principles of Art, such as repetition, pattern, balance, movement, and contrast, may be used more pointedly in realistic narrative films. Using the elements and principles wisely will lead to better still shots and a better overall film.

Using Film in the Classroom

Guiding Questions

Why should film be used in the art room (or any classroom)? What are the ideological differences between educational videos, mainstream “tent pole” films, and films that offer “elevated understanding of all cinema” when used in the classroom?13 How do films (and art) use the classical paradigm and realistic narratives? How can we use film to teach students how to properly use framing?

The Why of it All

This unit strives to help students liberate themselves and aim for a positive future using film as the catalyst. According to Bergala, “The most beautiful films to show children are not those in which the filmmaker tries to protect them from the world…,” rather the child in the film “plays the role of buffer, intermediary, in this exposure to the world, to the evil in the world, to the incomprehensible.”14 Directors have the ability to instruct child actors, integrating them in the realities of the world, “unprotected”, as they truly would be if it were a real life situation. Sometimes directors use real life situations and drop their entire story line into it, showing the reality of evils of the world while the actors themselves are assumed to be relatively safe. Exposing children to the evils of the real world through film allows them to experience the trauma second hand, the character confronting the world for them, keeping them safe while showing them how harsh reality can be. Having students relate to the adversity of others increases empathy and allows them to look at their own difficulties thoughtfully and intentionally. As well, students will be able to identify the choices that the youth in the films made and what their outcomes were and imagine what they might have been if the character had made a different choice. Through exposure to films that identify some of the difficulties that children face around the world, students will identify such things as ideology, story, and components of “mise en scene”. With the shared film experiences and a better understanding of what goes into a realistic narrative piece, as well as knowledge of setting the stage, students will use what they have learned in this unit (and others) to eventually create their short films that will be presented for their year-end final.

Ideological Differences between Film and Videos in the Classroom

Most students are exceedingly familiar with modern movies in the theaters and on television. Some teachers use movies as a “reward” or (far too often) to loosely relate to a lesson or unit in order to give students something “fun”, and then some teachers use movies as a teaching tool. In education we typically use cinema because it can capture the attention and imagination of students and because it is “immediately perceptible, visible, audible…”15 With streaming services so easily accessible viewing movies has become increasingly simple but does not have to be increasingly useless. Because of the immediacy and wide range of stories and ideologies, films are an excellent way to introduce ideas in the classroom when used intentionally. Film must be a part of a greater whole, used to make connections and increase understanding through discussion and analysis. These connections can broaden students understanding and knowledge of the world at large and also open them up to new ways of experiencing and connecting with the world in the future. Films can provide the magic of enabling a student to be in and see our world in new ways.

In the classroom, we use educational videos such as Bill Nye or Khan Academy to provide layers and address different learning styles. These types of videos may be used as an introduction to what will be taught next, add supplemental information and ideas to what is already being taught, or to reiterate what’s been already taught. Educational videos are typically explicit with facts and stories, graphs and data, with clear purpose and intention.

Mainstream “tent pole” films, as described by Bergala, are the mainstay of major movie theaters today.16 The DC vs. Marvel Multiverses are excellent examples of this, and create a “tent pole” city all their own. They are meant to excite and thrill, often bending the boundaries of good and evil. Each movie will generally end in a cliffhanger or, like Marvel movies, have extra snippets at the end giving a teaser for what will be coming to theaters near you in the future. Unlike more artistic films, “tent pole” films do not require a child-viewer to process information to understand the more complex issues presented. These films are also less likely to present real life issues, complications, and experiences, or a realistic world view, much less a real look at children and their real life experiences.

Artistic films that offer more elevated learning in the classroom, or films that teach, will stimulate curiosity and intuition differently and more intensely than “tent pole” films. Most students want high action, drama, and special effects, or the simple, easy to follow, storylines of the mainstream film; however, the category of film being used in this unit is more likely to make the student think, feel, contemplate, compare, contrast, and put themselves (mentally) in the shoes of the characters involved. Using artistic films in the classrooms allows students to increase their awareness of and responsiveness to the world outside of themselves. Bergala states that most often the classroom is the only place where students will be exposed to the implied lessons of film in this category, so these lessons may be understated.17 Regardless, films such as Daughters of the Dust (1991 USA), Where is the Friends House? (1987 Iran) and Wild Child (1970 France) are more likely to offer elevated learning than the likes of any Batman or Spiderman movie when used in the classroom. Realistic narrative films operate through subtle and intentional use of mise en scene. Students can learn to bring their attention to how a film develops, how it looks, and how it makes them feel. That is the goal.

The Classical Paradigm and Realistic Narrative

Most students at the high school level know that a good story has a beginning, a middle, and an end. They may also know that the rising action, the climax, and the resolution are parts of the “classical paradigm” where a “narrative model is based on a conflict between a protagonist, who initiates the action, and the antagonist, who resists it.”18 Within a realistic narrative, the story may follow the classical paradigm but is more likely to bury the “and then” within the story, with the series of events seeming more random and episodic than a life-ending problem after a life-ending problem to be dealt with, as is the way of a mainstream action film. “Realists prefer loose, discursive plots…we dip into the story at an arbitrary point”, we then see a small slice of real life, and the film ends and life just goes on.19 We don’t really know what comes next: maybe they live, maybe they die, maybe they go, and maybe they stay. We are left to wonder about what happens next on our own, not expecting a part two or an epilogue in most cases. Where the classical paradigm typically ends with a resolution of some kind, a realistic narrative often does not.

Suggested Films for Realistic Narrative

The film A Time for Drunken Horses (Iran, 2000) is an excellent example of a realistic narrative and a paradigm, just not a classical paradigm.20 As if living in a war-torn Kurdish village between Iraq and Iran wouldn’t offer enough rising action scene after scene, the main characters in this film are quickly orphaned and must find a way to survive and also obtain a life-saving surgery for their youngest sibling. As things are happening, one might think, “Ah, here is the solution!” but that solution, or the resolution of the classical paradigm, just never comes. This film follows more of a circular paradigm. The harsh realities of this film end with just more harsh realities for the viewer to contemplate. This film presents a persistence and drive that is mortifying and motivating at the same time. How could you live through all that, but also, how could you not try? That is reality.

The Little Girl Who Sold the Sun (Senegal, 1999) is a story about a young girl who truly knows her worth and isn’t afraid to stand up for herself.21 Sili Laam is crippled by polio and lives with her blind grandmother who sits on the street singing and telling stories for money. Sili decides to sell the government-run newspaper, the Soleil (Sun in English), to make money to support herself and her grandmother despite being harassed, pushed around, and threatened by the street boys that see her as competition. One local boy sees more in her and becomes a guardian and a friend. Unlike some of the other realistic narratives, this film ends on a more positive note with the notion that Sili is going to be just fine. She’s a fighter and she will overcome.

The Runner (Iran, 1984) is an amazing story of a young boy, homeless and alone, living on an abandoned and beached ship, who starts out collecting trash at the local dump and moves up in the world with each new job he starts.22 The young Amiro starts to collect bottles from the ocean (that uncaring tourists toss overboard from big cruise ships) until he is pushed around by a bigger boy and realizes he is being pushed out of the competition there. He decides to go solo selling cold water on the docks until he has to fight with and outwit a man who tries to steal his ice. He starts shining shoes where he is accused of stealing by an American tourist. Amiro does realize he needs to do something more with himself, so he enrolls in school to learn to read his beloved magazines about airplanes. Between his struggle to survive and the struggle to win in the wild competitions with the other boys in town, the film is sad, funny, and uplifting all at the same time. Most important is the look of the boy in his situation, a look that is framed in a mise en scene of extremes: fire, water, and desert.

There are many other realistic narrative films from all over the world that would be perfect for this unit. These are simply three out of the many viewed while creating this unit that stood out to this teacher as interesting and appropriate for high school students. Regardless of the film chosen, the teacher should always preview and prepare questions before showing a film. Finding specific spots to stop, talk about framing, aspect ratios, and mise en scene will be necessary.

Comments: