Part 1: American Indians

English speaking people have used a number of tropes or stereotypes to try to understand their interactions with Indigenous Americans. These tropes are a useful tool in interpreting images of Indians from the early colonial period through the early US Republic. The five tropes that we will examine are: The Natural Man, The Noble Savage, The Indigenous Ambassador, The Vanishing Indian, and the Romantic Indian.

The Natural Man

This lesson pairs with background information students have already learned about the earliest English colonies, places like Roanoke, Barbados, and Jamestown. The image is also discussed in the context of the late 1500s and early 1600s and Renaissance ideas about the New World and its people. The first impression English settler colonists had of Indians was that of the “Natural Man” who was friendly, pure, and was compared to the Picts of British prehistory. For visual examples of this trope students should look at the watercolor images by John White [especially those depicting the “werowance” and his wife and child 1585-1593] for examples of this kind of cautious admiration.2

We do not know if the people painted by White consented to being illustrated. We do not know if they posed for the artist, or for how long he interacted with each of them. The images, however, appear lifelike enough to have been drawn from first-hand experience.3 The image analysis starts with listing the things we can see in the watercolor. A bow, a quiver of arrows, a shirtless man, with tattoos, a necklace, bare feet, etc. The next step is to try to go one step deeper and ask students to decide the extent to which they think the images are objective. John White depicted the Indians of Virginia in poses familiar to European audiences, with weapons that were recognizable.4 The images were created for an audience of potential colonial investors, and with the intent of showing the pleasant and friendly Indians that would meet future settlers.5

The Noble Savage

This lesson pairs with the 17th and 18th century colonial period. Students can make connections to their earlier study of the Enlightenment debates between Thomas Hobbes and Jean-Jaques Rousseau. Elite colonists were influenced by these ideas, and this influenced the way they viewed the Haudenosaunee and Algonquian peoples they encountered. Rousseau’s ideas about the corrupting influence of “civilized” society and the basic tendency of people towards liberty and equality influenced painters such as Jan Verelst and Benjamin West.6 The Indians in these paintings are shown as noble and wise, because of their relative liberty and self-imposed moral framework. In this context, these men are valuable (and noble) allies for the British in fights against the French.

The two major works to examine here are Four Indian Kings painted in London by Jan Verelst in 1710, and the Death of Benjamin Wolf painted by Benjamin West who had been in America and had observed details there to lend truthfulness to the painting.7 These two paintings represent a view of American Indians from an informed distance across the Atlantic. Jan Verelst met the men he painted, and Benjamin West lived in America and based the details in his painting on objects he obtained while there.8

Image analysis starts with listing the details students see in the painting. For example, in the Death of Benjamin Wolf, an indigenous ally of the British is depicted in contemplative pose in the left foreground. Students should be directed to notice the details of the man’s tattoos, hairstyle, and beaded bag as ways to identify him as a Mohawk Soldier. The Realism of his muscular body makes him human and relatable while his nakedness in contrast to the other soldiers clearly identifies him as an Indian. The Battle of Quebec was fought in September, when battling nearly naked is not practical, however Benjamin West shows the generic Indian’s “nakedness” for reasons of moral messaging about the nobility of the technologically backward, but pure morality of the native people of America.9 After students examine the image in detail it is important to reveal that the man depicted was not based on any actual Mohawk man. It is not a portrait of a specific individual, instead it is a trope, based on ideas, Greek and Roman statues, but not on real life.

The Indigenous Ambassador

In the period between the French and Indian War (Seven Years War) and the War of 1812 the 13 colonies developed into the United States. This period of wars and conflicts can be understood as a constant struggle between three major populations, the British, the Indians, and the Colonists. Students will have read and learned about the adventures and exploits of mythical heroes such as George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, and James Madison. However, these men would not have been able to create the USA without assistance and alliances with Indigenous men. Thayendanegea (called Joseph Brant by most English speakers) was a Mohawk ally against the French.10 Ut-ha-wah (sometimes called Captain Cold) was an Onondaga chief of the Haudenosaunee Confederacy who helped the American Republic fight against the British in 1812.11

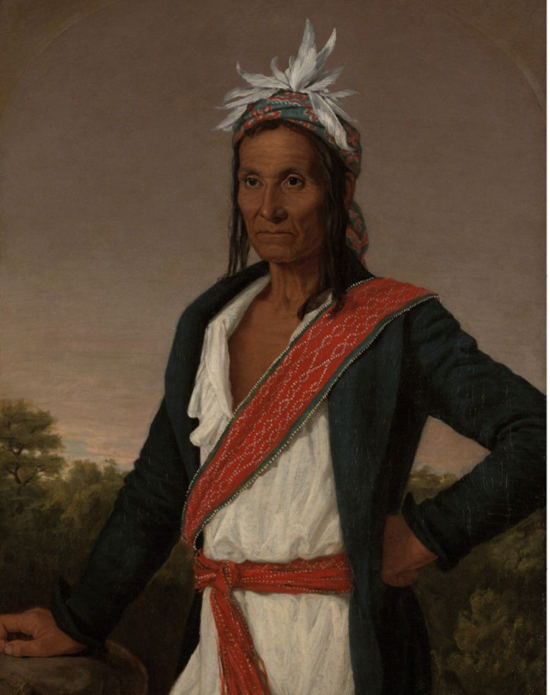

[Captain Cold, or Ut-Ha-Wah (Onondaga, ca. 1770-1845) Artist William John WIlgus (American, 1819-1853)]

This period in US history is filled with “great men” who are described as mythical heroes in history textbooks. Thayendanega and Ut-ha-wah offer an alternative pair of heroic men who served to usher the new country into being. Portraits of these men can be analyzed for hints at these men’s hybrid cultural status as a cultural bridge between the Haudenosaunee Confederacy and the United States. These portraits can be examined in parallel with a lesson on the influence the Haudenosaunee (sometimes called Iroquois) Confederacy had on the formation of the US government and the philosophy of the founding fathers.

The portrait of Ut-ha-wah can be analyzed for clues to the hybrid identity of these men who were cultural ambassadors and military allies. We do not know if he sat for this painting, or the conditions under which it was commissioned, but the realism and detail of the image lead us to believe in his humanity. We can “read'' several details in this work that can be used to understand the hybrid status of an individual of his stature. The diagonal red sash evokes wampum belts, which were used as a means of communication and treaty-making.12 The feathers on his head were called gustoweh and were an Iroqois tradition.13 Which clearly marks him as part of the Haudenosaunee culture. He is wearing a white ruffled shirt and dark blue coat which identify him as participating in the clothing traditions of the Anglo-Americans. It is also important to note the symbolism of his posture and how Ut-ha-wah is standing in front of the American wilderness, almost as though he is the gate-keeper of access to the land.

The Vanishing Indian

In the early nineteenth century the US Republic began expanding its claims to inland territories. Cities and settlements grew, and US Americans demanded increasing amounts of land to build family farms and plantations. After the War for Independence, the Indians who had once stood in the way, no longer had French allies or “Redcoats” to support them.14 From the perspective of the US Americans the Indians seemed to be “vanishing.” Some Amerindians fled to Canada in the wake of the US war for Independence, and others fled west like the herds of Bison that once roamed as far east as the Appalachians. From the perspective of east-coast cities, the Indians were either leaving or dying out.15

There was a third option though. Some Amerindians were blending in. The so-called “Civilized Tribes” of the Southeast were adapting. The Cherokee, Choctaw, Creek, Chickasaw, and Seminole were determined to stay in their homelands and chose to adopt Anglo-American lifestyles and clothing. This process can be seen in paintings of individuals such as David Vann, a Cherokee Chief, and the 1827 portrait of Sequoyah, a Cherokee scholar, and the “father” of the Cherokee written language. These men were almost indistinguishable from their US American contemporaries, were it not for some details of their dress or language that give away their Indigenous identity. Fringe on the collar of a coat, or the wearing of a turban serve to indicate their identity as Cherokee while their white shirts, cravat, hairstyle, or in the case of Sequoyah, his quill pen, tell us they identify as part of “American” society.

The Romantic Indian

Just after the Jacksonian period of Indian Removal, and the creation of the Oregon Trail by early fur traders, but before the westward movement of large numbers of “pioneer” settlers there was a cultural shift towards viewing the Amerindians of the west as romanticized symbols of the death of their way of life. This period corresponds to an increase in industrialization of the cities of the east, and the romantic movement in literature, music, and art. Students can connect the paintings in this section of the unit to studies of cultural reformers, and the Second Great Awakening.

[George Catlin, Máh-to-tóh-pa, Four Bears, Second Chief, in Full Dress 1832 Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of Mrs. Joseph Harrison, Jr., 1985.66.128]

Indigenous movements against the influence of U.S. American culture such as the spiritualism of Shawnee Prophet Tenskwatawa, can be visualized in the paintings of George Catlin and Karl Bodmer of the Mandan and Sauk. The portraits of Mandan Chief Mah-to-toh-pa/ Mato-Tope (Four Bears) can be examined as examples of a sense that the Amerindian “way of life” was soon to go extinct. These images are especially important in gaining insight into the perspective of the Mandan leader himself. He chose the way he was depicted and sat for the paintings wearing clothing and accessories he selected for himself.16

There are four major portraits of Mato-Tope that can be examined in this portion of the unit. Mah-to-toh-pa, Four Bears, Second Chief, in Full Dress can be used as an example. Investigation of these images should start with asking students to list the details they see, and then progressing to deeper questions about why this man chose to dress like this for the portrait. Mato-Tope arrived for his portrait sessions dressed how he wanted to be portrayed. He met with Catlin and Bodmer separately several times and was interested in crafting the way he was depicted. He selected his clothing and pose to express who he was and what his culture was. But it is important to remember that white Americans were the audience paying the artists. The Mandan people were experiencing a period of great change when these portraits were made. Contact with fur traders and other US Americans increased, and it seems Mato-Tope himself was aware of the fleeting nature of the lifestyle he was living.17

Conclusions about Amerindians in portraits.

The goal of this unit is to pull together student understanding of white American perspectives and stereotypes about Amerindians, with the nearly hidden Amerindian self-expression that sneaks out of these historical images. Even in a period of US history that subjected native people to the diseases, conquest, and violence of settler colonists, the humanity of the men in these portraits can still be appreciated.

Comments: