Part 2: Afro descended and mixed-race women

The clothing and body decorations a person chooses to wear project a certain sense of self to the world. Some aspects of appearance convey gender, some convey status. The more control someone has over their appearance the more you can "read '' something about how they saw themself. For individuals who have little to no control over their appearance, the details are where they wield their limited agency.18

American History books are full of images that use pathos to emphasize the incredible violence and dehumanization done to the people who were enslaved. This part of the unit is designed to humanize and make African descended people in the Americas more relatable. Students often start my class assuming all black people in history were enslaved which is why it is important to show that enslaved was not the condition of all people of African descent in the Americas.

This nuance is difficult for some students to understand. The images in the four parts of the second half of this unit look at a few different angles on the concept of race, skin color, and status. These categories played out differently in the United States compared to Iberian and French colonies, and the US versus the Caribbean. By comparing events in the US with contemporaneous images in other regions, my hope is to show the diversity of experiences across places at the same time.

The four topics of this half of the unit are explained using a selection of historical images. The first topic is an examination of the variety of specific racial categories or “castas” in Latin American colonies compared to the literally “black and white” categories in the United States. The second topic is the “Tignon Law.” A restrictive dress-code that was appropriated by women who were forced to cover their hair in public. The third topic is the population of free people of color in the eighteenth century on the island of Dominica (not Saint Domingue, or Santo Domingo–which confuses students at first). The fourth and final topic is that of “fancy girls” who were enslaved women sold for their specialized skills.

Unreliable racial categories Latin America vs the U.S.A.

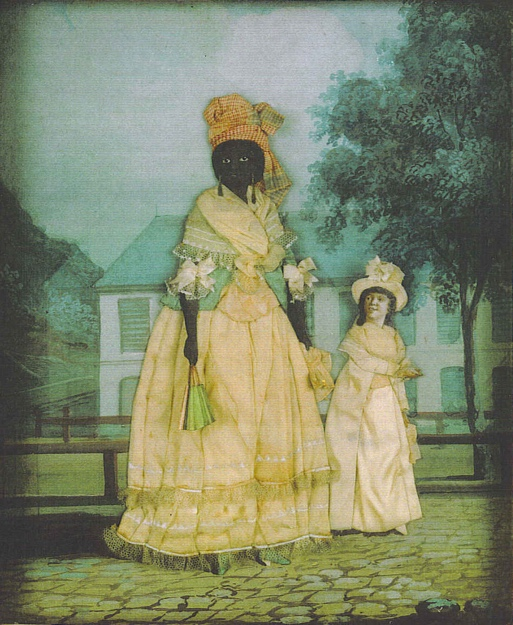

[Free woman of color with quadroon daughter; late 18th century collage painting, New Orleans. Artist unknown]

This public domain image titled “Free Woman of Color with her Quadroon Daughter” is a good place to start the discussion of racial categories and identity. In New Orleans, where this painting was made, the racial categories were determined by the percentage of “black” parentage. Terms like Quadroon and Octoroon were used to describe people who were one-quarter or one-eighth black.19 In Spanish and Portuguese America there were specific and detailed categories that named biracial people as Mulatto, Morisco, and Chino. These terms existed alongside even more offensive ones such as “Cambujo” for a particularly dark-skinned black man, or “Loba” (wolf) for a non-specific mixed race person.20

The Casta paintings of Miguel Cabrera are a good place to start with student analysis of racial categories. Students will make detailed observations and describe the people in the images. They should also speculate as to whether these images were based on real people or stereotypes. Comparing the Casta paintings to the Free Woman of Color in New Orleans can also start the conversation about stereotypes versus the people who lived with these labels.

[Isaac and Rosa, Emancipated Slave Children, from the Free Schools of Louisiana, 1863-1864 Albumen Print by Myron H. Kimball]

Racial Categories in the USA were literally more “black and white.” Images such as this photo of two young children— Isaac and Rosa, slave children from New Orleans—were used by social reformers and abolitionists to argue against enslavement. Despite their appearance, both children would have been legally “black.” In the US children of enslaved women were considered to be enslaved regardless of their skin color. Race based hereditary enslavement laws date to the aftermath of Bacon’s Rebellion in 18th century Virginia.21 Because enslavement was associated with racial categories, the “One-drop Rule” came to define any person with at least “one drop” of “black blood” legally black. The Focus for this lesson is on the concepts of Colorism versus Racism. Students will read an excerpt from “Who is Black? One Nation’s Definition” By James Davis and explain how it was possible for people who appeared to be “white” could be legally “black.” 22

Self expression and Tignon Laws

The next question students should be confronted with is “If people who looked white were legally black, how did anyone know?” When New Orleans switched from French to Spanish control, “one major concern was that free Black women were too beautiful, and too many white men were attracted to them. In 1786, the governor of Louisiana proclaimed that all free Black women must wear tignon to make them different from white women.” This so-called “Tignon Law” (pronounced TEEN-yon) required all black women to cover their hair to delineate which women they were, as well as to limit their attractiveness.23 Women of color in the region appropriated the style and used it as a symbol of beauty, resistance, and a proud association with West African traditions of head-wraps and turbans.24

Images of women wearing Tignons can be analyzed as a class, and students are encouraged to think about whether the women in these portraits are victims, confident agents of their own destiny, or something else? Class discussion can make connections to the Native American Studies concept of “survivance”, or the idea of appropriation by a subaltern population. Students will be encouraged to think of times when a restriction was used as a source of pride by a marginalized group and how this is different from “cultural appropriation” by the dominant population.

Settler Colonies versus Exploitation Colonies: Brunias’ Dominica

[Linen Day, Roseau, Dominica ca. 1780, by Augustino Brunias, Yale Center for British Art]

In the USA, enslaved people had little chance for manumission or escape from enslavement. Running away to another country—Canada or Mexico— were the only real options for permanent freedom.25 People of color in the West Indies are not often discussed in US History class, however the cultural and economic connections between places like Dominica, Martinique, and Barbados and Georgia and the Carolinas were close. Planters traveled between these places, sometimes bringing enslaved people with them.26

In the 18th century the thing that made the West Indies distinct from the 13 colonies on the continent was that they were exploitation colonies not settler colonies.27 This meant that the blended race offspring of master-slave sexual liaisons could be manumitted without disrupting the economy of the islands. In places like Dominica a large population of free people of ambiguous racial background lived in a parallel world quite different to that of the USA.28 Paintings and Prints by Augustino Brunias are a window into this world of high-status people of color. Their cotton and linen clothing—in varying degrees of fashionableness can be a way for students to analyze the relationships between the people in the images. It is worth pointing out that visitors from Europe were impressed with the luxurious clothing that was more affordable in the colonies.29 Darker skin tones seem to correspond to either the shabbier clothing of the enslaved or the livery of personal servants.

Fancy Girls dressed for the White Male Gaze

Now the unit returns to the US southern states and the image of the slave auction. However, the images used are not those of naked people in chains. The goal here is to convey a kind of unseen trauma, that of so-called “fancy girls.” Women who were sold as domestic servants with “special skills” such as sewing, cooking, or child care would have to look refined. There also was an understanding that the older definitions of the phrase “to fancy” was a contraction of the word “fantasize” and that these women were also destined to a future of sexual exploitation and violence.30

Enslaved Women were dressed in colorful calicos to increase their “sale” price at auction. Paintings such as Slave Auction, Virginia by LeFevre J. Cranstone (1862) or Slaves Waiting for Sale, Richmond, Virginia by Eyre Crowe, show women dressed in clean bright colors. The Cotton from the fields that other enslaved laborers had grown, picked, and processed, had traveled to the cotton mills, textile factories, and back to Virginia in the form of textiles that dressed enslaved people to make them more appealing to potential buyers.31

Students should pay special attention to the way the white men seem to be interacting with the women. The posture and facial expressions on these women who did not choose to be painted, did not choose the clothes they wore, and certainly did not choose to be sold like some kind of prized livestock.

Conclusions about African descended women in portraits.

Comparisons to the images of Amerindian men from earlier in the unit can be made, and students should consider whether we can see any kind of truth in these images despite the lack of agency the individuals had over the mode, or manner of their depiction. These works are intended to reinforce the real human identity of the people in these images. To understand and appreciate the marginalization they faced and the ways in which they were victimized, while also seeing them as fully active participants in their own lives. None of the images is a self-portrait, and we cannot directly hear the words and opinions of these people, understanding their clothing, and seeing them for who they were is a start toward appreciating their humanity.

Comments: