Teaching Strategies

Comic Book Poetry

Comic poetry or poetry comics is a hybrid creative forms that combines aspects of comics and poetry. It draws from the syntax of comics, images, panels, speech balloons, in order to produce a literary or artistic experience similar to traditional poetry. “Use of the terms comic poetry and poetry comics is widespread among its practitioners. Alexander Rothman, editor-in-chief of Ink Brick has written, “I call the work that I make and publish ‘comic poetry’. At the end of the day, more than any other practitioner a poet is dealing with words.14 Words aren’t necessary for comics, but of course they’re there to use. Panels aren’t necessary, but they’re also there to use. Where the poet's toolbox contains every imaginable arrangement or manipulation of words, the cartoonist holds analogs for the visual element of the page.” Comic poetry traces its origins to illuminated manuscripts, graphic novels, concrete poetry and poets who combined images and text such as Kenneth Patchen,15 According to artist and scholar Tamryn Bennett, “The term comics poetry can be applied to a growing field of works that fall outside of traditional definitions of both comics and poetry.”

I suggest to students that once they begin drawing your poetry comic, think of your story as if it were a movie that you can split up into small scenes. You can then draw each of these scenes in a separate box on the page. Then boxes are called panels. You can draw each panel on a separate sheet of paper or use large construction paper (see my students’ illustrations). Your panel borders don’t have to be very precise, so don’t even worry about using a ruler.

Poems to See By

Poems to See By is a text that I’ve used to demonstrate to students how poems can be interpreted in graphic form. Students truly get to visualize how we see poetry as an object. The author, Julian Peters is a comic artist16 who interprets great poetry in which he puts a cool twist on twenty-four classic poems from Langston Hughes, Gwendolyn Brooks and Carl Sandburg. These are poems that can change the way we see the world and encountering them in graphic form promises to change the way we read the poems. In an age of increasingly visual communication, this format helps unlock the world of poetry and literature for a new generation of reluctant readers and visual learners. Grouping unexpected pairings of poems around themes such as family, identity, creativity, time, mortality and nature Poems to See By could also help my students see themselves and the world differently.

Reader’s Theater

Reader’s theater is a collaborative strategy for developing oral reading fluency through reading parts in a script or book. Students don’t have to memorize their parts but need time to read their parts several times in order to get comfortable with the language and add appropriate expression. I would suggest involving dialogue between characters. This really helps students bring characters to life and when students work together they foster collaborative environments.

- Students practice reading aloud, which helps improve fluency the ability to read with accuracy, speed, and expression.

- By performing a script, students gain a deeper understanding of the text, characters, and plot.

- Reader’s theater involves collaboration students work together to bring the script to life, fostering teamwork and communication skills.

- The interactive and dramatic nature of reader’s theater tends to engage students and make reading a more enjoyable experience.

- Participating in a performance boost students’ confidence in public speaking and presentation skills.

Improvisation

Good Improv in the drama classroom requires: Time and practice: time and practice is needed to become good at this.

Freedom and space to be silly: students should feel free to express themselves, good improv requires risk taking so students need to feel comfortable. I suggest using energy release whole class circle games.

Confidence in dialogue and storytelling: Good improv is about making and accepting offers with dialogue. Creating dialogue spontaneously is a scary thing, and I find students feel safer and more confident. I suggest group scene creation activities.

Working together: The more trust there is in the class, the better the improv will be.

Key Improv terminology: The following improv terminology is more focused on building improv skills.

Offer: An offer of an idea for the scene. This may be an offer relating to a character’s characteristics (e.g. I think I twisted my ankle) or a scenario or point of action offer (e.g. “that truck just flipped over and is headed our way”) which provides an idea to continue the scene.

Accepting: As the name suggest, this is where you accept an offer within an improvisation and run with it.

Alternative Offer: This is where students do not “block” an offer but make an alternative offer to progress a scene. There is a fine line between making an alternative offer and blocking and it has to be modeled for students.

Blocking: The opposite of accepting. This is where someone rejects the offer or idea for the scene.

Building: Related to accepting where an offer is build upon within a scene or the idea is expanded.

Endowing: is an improvisation technique where you give (offer) characteristics (personality traits, attitude, mood, physical attributes, scenario) to another character during a scene. It is basically giving the other person information about their character or the scene.

Discussing the terminology with students really helps create authentic improv moments.

Sound of Poetry

Explain to students that making comparisons between things and using metaphors is often used in poetry. This is because when we write poems, we want to communicate strong emotions and paint a vivid picture to share in the poem. It is helpful to use the most descriptive language possible to get the person who is reading the poem to really feel and understand what you are trying to convey. A good way to do this is to use comparisons and metaphors.

Comic Poetry Brain Starters:

- Do you have difficulty making new friends?

- What are some traits of a good friend?

- Choose 5 of the following emotions that explain how you feel when you and your friend share secrets: overwhelmed, anxious, scared, joyful, or excited.

- Choose 5 of the following emotions that explain how you feel when a friend betrays you. Jealous, guilty, betrayed, calm, or disappointed.

- How did you feel when we visited the school on the north side of town for the basketball game and the opposing team had a brand-new gym, the team and cheerleaders also had brand new uniforms?

Poetry and Animation with Harold and George in Captain Underpants

The Adventures of Captain Underpants by Dav Pilkey is the first book in the Captain Underpants series, published in 1997 (Dav 1997). It follows the adventures of fourth graders George and Harold, who are best friends. They love to pull pranks and play tricks on others. They also write their own comic book about a crime-fighting superhero named Captain Underpants which they sell for 50 cents at school. They find a magical ring and use it to hypnotize their school principal, Mr. Krupp into becoming Captain Underpants. Captain Underpants fights for truth and justice. Even Captain Underpants doesn’t know his true identity.

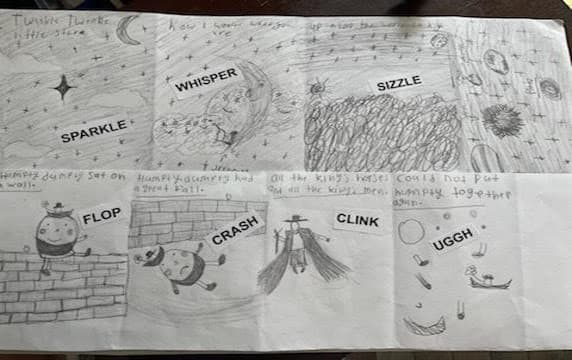

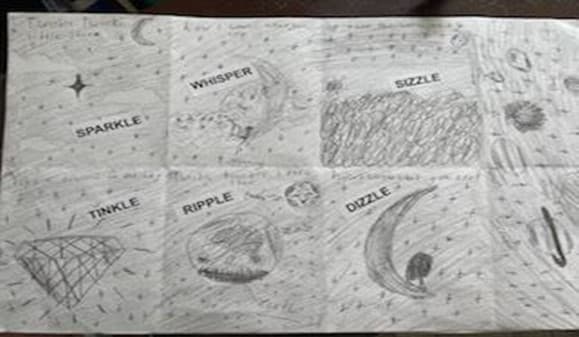

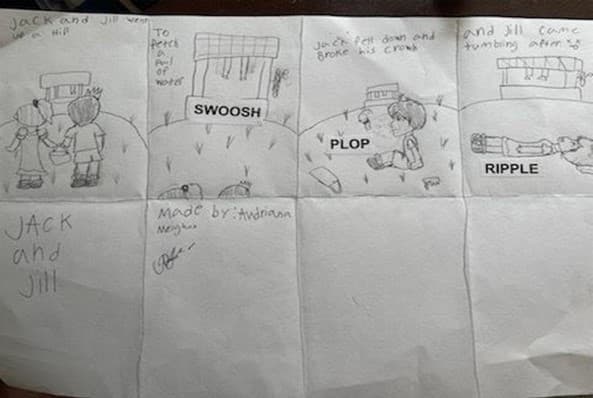

Examples of my Students Comic Book Poetry using Sound Device of Onomatopoeia

In this lesson my students used several nursery rhymes such as “Twinkle, Twinkle Little Star,” “Humpty Dumpty,” and “Jack and Jill.” My students were so excited and engaged in creating these nursery rhyme comics. You can see that a couple of students mastered the objectives in the following illustrations and demonstrated full understanding of how to create the comic sections using onomatopoeia. Onomatopoeia is a word or group of words that imitate the object being described. Words like buzz and hiss are obvious examples.

Student A provides their comic interpretation of nursery rhymes Twinkle, Twinkle little Star and Humpty Dumpty.

Student B provides their comic interpretation of nursery rhymes Twinkle, Twinkle little Star.

Student C provides their comic interpretation of nursery rhymes Jack and Jill.

Reader’s Theater: Henry Box Brown Student Performance

Then, let them form small groups and take five minutes to act out what they have read. To spice up this exercise, you can have one group mime the scene, another group have a narrator with actors, and yet another group employ dialogue taken directly from the reading. Students can’t act out scenes if they don’t comprehend the reading; acting out a scene or story helps them connect with the material and offers a concrete way to start making sense of it. For reluctant and hesitant readers (including those students just learning English), acting provides a more concrete way for them to understand the stories.

Reader’s Theater Process

Character Assignments: Each student is assigned a specific character from the text or script. Students will work in small groups so that each student has an opportunity to perform. Students will take turns reading various sections

Rehearsal: Students will practice reading their lines with expression, paying attention to tone, pacing, and intonation. They may rehearse in their small groups or individually.

Performance: The class performs the text/script as readers theater during open house or reading night.

Think-Pair-Share

Think-pair-share is a technique that encourages and allows for individual thinking, collaboration, and presentation in the same activity. Students must first answer a prompt or essential question on their own and then come together in pairs or small groups, then share their discussions and decisions with the class. Discussing an answer first with a partner before sharing maximizes participation, and helps to focus attention on the prompt given.

Step 1 Think

Begin with a specific question, and give students time to individually think about the answer, and document their responses on their own, either written or in pictures. Students can be given one to three minutes for this part of the exercise.

Step 2 Pair

Students are instructed to get into pairs. Decide beforehand whether you will assign pairs or let students choose their own partners. Remember when pairing to think of students and their personalities. Ask the students to share what they came up with, with their partners and discuss. You can provide questions for the students or have them ask one another. This part of the activity can take five minutes.

Step 3 Share

This part requires the class to come back together as a unit and host a whole class discussion. You can either choose to have one person report out from each pair or group with the class or the discussion can be more open. Students can also share with the class what their partner said.

Benefits

Think-pair-share is a simple technique that enhances students critical thinking skills, improves listening and reading comprehension and helps with collaboration and presentation skills Students who are typically shy may feel more comfortable sharing with the class after sharing with a partner, and students who are outspoken will benefit from first listening to others before sharing their own opinion. The think-pair-share strategy can be used at a number of different times within the classroom, such as before introducing a new topic to assess prior knowledge, after reading an excerpt or watching a film to encourage opinion formation and critical thinking, or before students begin an assignment, to help them gather ideas.

Comments: