Classroom Strategies

The CSI Approach

The CSI approach asks students to become Content Scene Interpreters. In becoming a CSI students must know what questions to ask, when to ask them, and how to ask them. The second part of the process requires that students know how to shape the information obtained from their investigation into a narrative like a historical detective would. To have students uncover historical information (to obtain information about literary characters) it is necessary to turn an historical episode, event, or person into a cold case.

Characters will be isolated in the sense that students will employ a CSI (Content Scene Interpreter, Williams 1 6) approach to help students discover:

1.Who is the person or what was the event?

2.What was the economic influence of the person or what were the economic consequences of the episode or event?

3.What was the political influence of the person or what were the political consequences of the episode or event?

4.What was the social significance of the person or what were the social consequences of the episode or event?

5.What is the relationship of the person or event to a specific community or state?

Cold Case #258 (Adaptation Julius Caesar)

Born on the Thirteenth of July around the year 100bc into a noble Roman family. I am considered one of the most able leaders the world has ever known and my name has forever become synonymous with power and leadership. The Russian word "czar", the German Kaiser, and the Arabic qaysar, meaning king or ruler are all variations of my name. The month of July is also named after me. As a young man I left Rome to travel to the Greek city of Rhodes, where pirates captured me and did not release me until a large ransom was paid for my freedom. I retaliated by gathering a private naval force, capturing the pirates, and crucifying them. Afterward, I moved steadily up the political ladder in Rome, holding a number of important posts, which culminated in my election to the post of consul in 59 B.C. Between 58 B.C. and 50 B.C. I conducted a series of brilliant military campaigns that won for Rome all of Gaul (modern-day France) and extended Roman power as far North as Britain. Members of the nobility, or patricians, in Rome came to fear me because I commanded a large army made up of fiercely loyal troops and was much loved by the common people, plebeians, of the city. Fearing that the people would make me king and overthrow the public, the senate voted on January 1, 49 B.C. to have me lay down my command. I refused. Was my refusal a precursor to my ambition to become king? Or was the Senate insanely jealous of my relationship with the commoners? What was the true motivation of the conspirators who lured my noble friend to betray me? You decide.

Textual, image, and other sources are provided to help students craft their account of the incident. Additionally, students are encouraged to find other pieces of evidence to help with their final determination. Students' explanations should include social, economic, cultural, and political factors that have contributed to their findings. Their findings must back up their conclusions with evidence from the crime "content" scene.

To get started with the CSI Approach, follow these steps in constructing a Cold Case:

1.Identify a person or event of local or national import, or both.

2.Establish the ESP of the person or event.

3.Select primary sources to serve as evidence for your case

4.Correlate your findings with your state content standards.

5.Begin building your case.

Text Reformulation

Text reformulation or Story Recycling (Feathers) 1 7 is a strategy in which students transform a text into another type of text. Whether students turn expository texts into narratives, poems into newspaper articles, or short stories into patterned stories such as ABC books, reformulating texts encourages students to talk about the original texts. In addition, reformulations encourage students to identify main ideas, cause and effect relationships, themes, and main characters while sequencing, generalizing, and making inferences.

Putting the (Adapted) Strategy to Work

1.First, introduce students to the types of texts they can use as patterns when they reformulate a text.

-If-Then Stories: "If the dog chases the cat, the cat will run up the tree. If the cat gets stuck in a tree, you'll have to get her down…" You might use, Laura Joeffe Numeroff, If You Give a Mouse a Cookie or If You Give a Moose a Muffin, to read as examples of if-then stories. This pattern helps students keep events in the correct sequence as well as identify accurate cause-effect relationships.

-ABC Book Structure: A is for ___________because___________. B is for____________ because____________." This structure works when students encounter a text with a lot of terms or when they need to pull out facts to remember.

-Repetitive Book Structure: In this structure, the reader sees a text structure that repeats throughout the book, as in Romeo and Juliet, the use of English sonnets. This structure helps students see cause and effect connections.

2.Second, model several types of text reformulations. Some students always choose to do patterned text reformulations; others students, though, begin to explore and benefit from various types of reformulations. Students might try the following reformulations:

-all types of texts into patterned texts, comic books, letters or interviews

-poems into stories or letters

-stories into plays, radio announcements, newspaper ads, or television commercials

-plays into poems or newspaper articles

-expository into narratives

-diaries/memoirs into plays, political cartoons, mini biographical sketches, or television newsmagazine scripts

3.Decide whether you or the students will choose the type of reformulation.

-It is important to achieve a balance with this strategy. Since the power of the strategy comes from deciding exactly what type of reformulation works best it is necessary to provide students options when working with specific text structures. Other times, when you want students to look at characterization, an interview reformulation would be a perfect fit.

4.Provide opportunities for practice and evaluation.

-Text reformulation works must be used repeatedly for students to realize its full benefits. These reformulations can be used to evaluate students' progress.

SPAWN

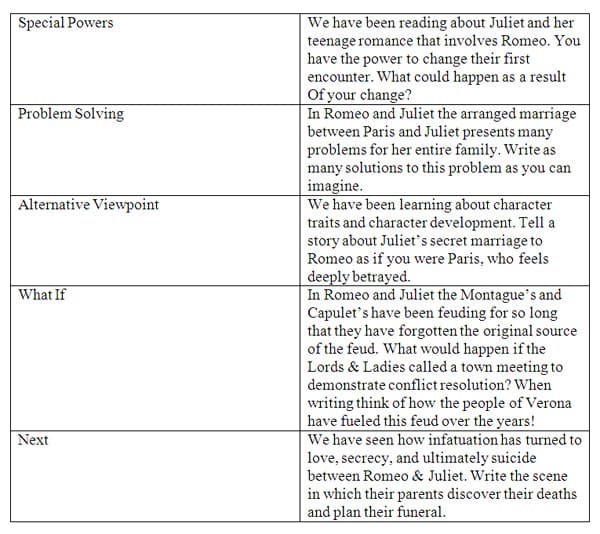

SPAWN (Martin, Martin, & O'Brien) 1 8 is an acronym for special powers, problem solving, alternative viewpoints, what if, and next. Each is a category of writing prompts that encourage students to move beyond the recall level of thinking. Each category is explained below:

S Special Powers: Students are given the power to change an aspect of the text or topic.

During writing, students should include what was changed, why, and the effects of the

change.

P Problem Solving: Students are asked to write solutions to problems posed or suggested

by the books and other related sources.

A Alternative Viewpoints: Students write about the topic from a unique perspective.

W What if: Similar to special powers, the teacher introduces the aspect of the topic that

has changed, then asks students to write based on that change.

N Next: Students are asked to write in anticipation of what will be covered and discussed

next. In their writing, students should explain the logic of what they think will happen

next.

Adaptation of Strategy for Romeo and Juliet

These prompts are given to students on different days of the unit. Students write responses to them in electronic logs kept in emails or blogs on wikispace. These log entries are transmitted to the teacher so she can read and respond to them. This type of focused writing can help reveal a more complete picture of students' comprehension and learning.

Correspondence Enactments

Correspondence enactments (Wilhelm) 1 9 are any kind of composing that is undertaken in role. Correspondence enactments are powerful because they provide the student writer with a persona, a purpose, meaningful information, a situation, and an audience—all of which help him compose. Plus, writing in role requires careful reading; students know they need information from the text to advance their point of view. It also develops students' awareness of how texts are constructed, since they are to write formal letters, newspaper articles, memos, and so forth.

Correspondence Guidelines for Students

In this enactment activity, students are asked to become one of the characters from the text that is being read or a character who would have an interest or perspective on the issue at hand. The student will then compose a form of correspondence based on his or her experiences as the character.

Students may write:

-From a character in the text to a character in another text, situation, or era

-From a character in the text to an imaginary character, or vice versa

-From a major to a minor character

-From real people to characters

-From himself to a character

-From a character to the author

-From himself to the author

-Anything else they can think of….

Students must decide the purpose of the correspondence, what form the correspondence will take, the kind of stationery and envelope, the address:

Comments: