Equal Groups Problems

For problems with Equal Groups, the three basic components are the total product, the size of a group, and number of groups. Varying the unknown produces three types of problems.

Unknown Product/Total

Twelve packages of pencils are purchased. If each package contains 8 pencils, how many pencils are there in total?

In this example the number of groups is 12, and the number in each group is 8. The unknown is the total number of pencils, which allows us to set up the general structure: 12 × 8 = ?

Unknown Group size

Twelve packages of pencils are purchased. There are a total of 96 pencils. Each package contains the same number of pencils. How many pencils are in each package?

In this example, the number of groups (i.e., packages) is 12, and the total number of pencils is 96. The unknown is the number of pencils per group, which is the solution to the equation: ? × 12 = 96

Unknown Number of Groups

Pencils are solid in packages of 8. If you bought 96 pencils, how many packages did you buy?

In this example, the known values are the group size, 8, and the total amount, 96. The unknown is the number of groups, which is the solution to the equation: 8 × ? = 96.

Arrays or Area Problems

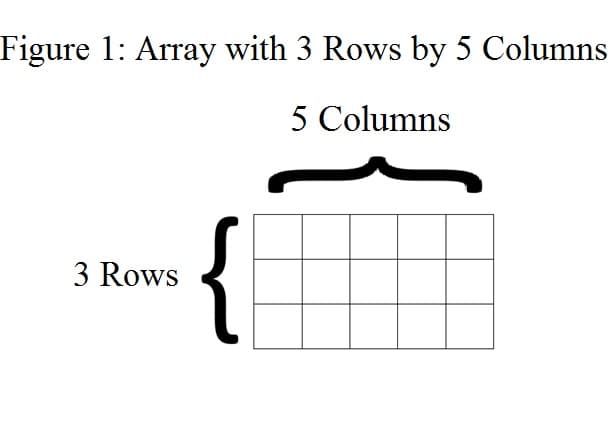

Multiplication and division problems involving arrays can include situations where the unknown quantity is number of rows, columns, or the total array. As outlined in the CCSS Glossary Table 2, area problems are arrays of squares that have been pushed together so that there are no-gaps or overlays (See Figure 1).

Array Size or Area Unknown

There are 5 rows and 6 columns of desks in a classroom. How many desks are there in total?

We know both the size of the rows, 5, and the columns, 6. To find the total number of desks in the array, we can use the equation: 5 × 6 = ?

Length/Row Unknown

There are 6 columns of desks and a total of 30 desks. Each column has the same number of desks. How many desks are in each column?

In this situation, we know the number of columns, 6, and the total number of desks, 30. The unknown quantity, how many desks in each column is the number of rows, which is the solution to the equation: ? × 6 = 30.

Height/Column Unknown

There are 5 rows of desks and a total of 30 desks. If each row has the same number of desks, how many columns of desks are there?

In this situation, we know the number of rows, 5, and the total number of desks, 30. The unknown quantity is the number of columns, which is the solution to the equation: 5 × ? = 30.

Multiplicative Comparison Problems

Comparison problems with multiplication and division use the concept of factors and ratios to define the relationship between two quantities. For compare problems, a ratio and quantity may be given in order for a smaller or larger quantity to be found or two quantities may be given in order to find a ratio.

Unknown Smaller Quantity

A gold cell phone costs $600. If a silver cell phone costs three times less than a gold phone. How much does the silver cell phone cost?

We know the greater quantity, the gold phone cost of $600, and are aware that the unknown amount is three times less than the greater amount.

We are able to set up the multiplication structure: Unknown × Factor = Greater; ? × 3 = $600.

Unknown Larger Quantity

A silver cell phone costs $200. A gold cell phone costs three times as much as the silver phone. How much does the gold phone cost?

We know the smaller quantity, the $200 silver phone, and the comparison factor, 3 times the silver, to find a larger unknown quantity, which can utilize the structure: Smaller × Factor = Unknown; $200 × 3 = ?

Unknown Ratio

A silver phone costs $200 and a gold phone costs $600. How many times more does the gold phone cost compared to the silver phone?

Knowing both the smaller amount, $200, and greater amount, $600, we look for the comparison ratio with the structure: Smaller × Unknown = Greater; $200 × ? = $600

Personalization of One-Step Problems

One context can be adapted into multiple problem types by simply changing what information is given and what information is unknown. Providing students practice with variations of the same scenario, especially if it is more familiar will potentially reduce student misunderstanding or confusion about the context and enable students to spend more time analyzing and solving problems. The budgeting personalized scenario I will be using best suits the equal group types and comparison types of one-step multiplication and division problems. The six problems that fall into these categories will be emphasized in the problem collection.

For example, examining the cost of just one of the types of uniforms can yield nearly all of the equal group type of problems.

Name Brand uniforms cost $32 each.

Question A: How many uniforms can be purchased with $10,000?

Question B: How much do 300 name brand uniforms cost?

Question C: If we want 450 uniforms, and we can spend at most $10,000, what is the most we can spend per uniform?

The brand of uniforms is intentionally generic here. In class, the brand names will be replaced with actual brands familiar to the students or actual brands that are being considered. In question A, the underlined dollar value can be changed to produce new equal groups – quantity unknown problems. In question B, the number of uniforms can be adjusted to produce new equal groups – total unknown problems. In question C, we can vary the number of uniforms we want and the total amount of money we can spend to suggest a price point for the uniforms. With question A, we can compare the number of uniforms that can be purchased with the number of athletes we need to outfit. Question B can lead to comparison of the product with our budget constraint. Questions C can lead students into comparing their result with the other options.

Comparison type problems lend themselves to the scenario when comparing the cost between uniforms. For example extending the situation to more options through questioning can look like:

Question D: T-shirts cost one fourth as much as the $32 Name Brand uniforms. How much do t-shirts cost? Question E: Name Brand uniforms cost how many times more than T-shirt uniforms?

The example above demonstrates how the problems themselves can introduce new considerations. However, depending on the relative preparedness of my students and their responsiveness to the initial problem context, I may choose to gradually reveal the three main options for uniforms at once, or allow students to problem solve their way to the new options. I would consider intentionally withholding information as students begin working within the context, in order to prevent some students from becoming too overwhelmed with the scenario. I anticipate some students who will complete these initial problems more quickly, and I would be able to provide them additional practice with variations of the problems by changing the values, givens, and unknowns while my co-teacher and I are able to help all students access the problems.

Comments: