Strategies

I will begin teaching the unit by introducing basic geometry, that is, symmetry. We will review symmetry and the different types of symmetry that exist. Then we will delve into fractals, with emphasis on the Iterated Function System (IFS) formalism for generating fractals. I will also talk about the application and examples of IFSs. In an effort to bridge the gap between mathematics and the real world, i.e. science, we will take particular look at an example of a human organ, the lung, which almost all of them are be familiar with by this time. I will also make sure that the students have studied about the lungs in their science class. This will make teaching the unit easier for me, and more satisfying for the students. First and foremost, we will talk about symmetries in nature. This will segue into our topic of fractals and the symmetries that exist in them.

There are three forms of symmetry we are familiar with. These are translational, reflectional, and rotational symmetry. Translational Symmetry is when a shape is displaced either horizontally or vertically. An example is a brick wall. Reflectional Symmetry is when a geometric shape can be split into two parts by a line, one half of the shape removed and the missing piece can be replaced by a reflection of the remaining piece. A perfect example is the human face. Rotational Symmetry is when a geometric shape is rotated about some point and its resulting image is the same as the original geometric shape. A common example is the geometric shape of a snowflake. Rotating it by 60 degrees will return the shape to its original shape.

After going over the basics of symmetry, we will take a look at the geometric attributes of simple fractals. In other words I will use the concept of self similarity to explain simple fractals.

Now that the students have reviewed symmetry and know what fractals are, they are ready to look at a mammalian organ, the lung, to see if there exist any forms of symmetry.

Symmetry in the Lungs

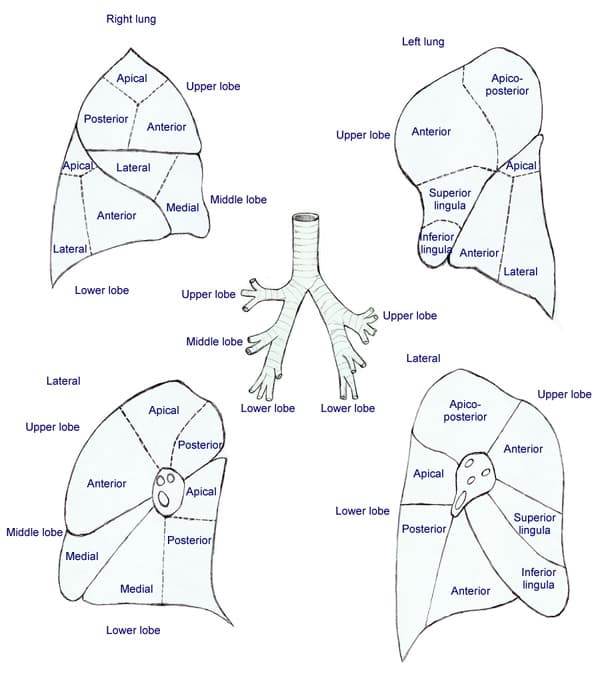

You can find some existence of symmetry between the right and left fragments of the lungs. Figure 2 shows how the right and the left lungs are subdivided into lobes. Each subdivision in the lobe is called segments. The right lobe has 10 segments. That is, 3 in the upper part, 2 in the middle part and 5 in the lower part of the right lobe. Just as the right lobe has segments, so does the left lobe. The left lobe has 8 segments. That is, both the upper and lower left lobe contains 4 segments. The diagram clearly labels the names of each of the segments in both the left and right lobes. The lobes are covered by the inner pleura, which is in contact with the outer pleura as it reflects from the lateral surfaces of the mediastinum. The inner pleura form introversions into both lungs, which are called fissures. These fissures are used to keep both right and left lungs apart and to do so, both lungs have 2 fissures. One of the fissures in the left lung, however, is incomplete.

Figure 2 the Human lung

The closest of the symmetries that exists in mammalian lungs is reflectional symmetry. As a quick classroom hands-on activity, we will use Geometer's sketch pad to make a sketch of the lungs. The goal here is to let the students become familiar with the organ that they are about to study. They will use the tools in Geometer's sketch pad to make copies of the lung sketches and position them in creative patterns. Now I will begin to introduce to the students fractals: both what they are and how to generate them. "I find the ideas in the fractals, both as a body of knowledge and as a metaphor, an incredibly important way of looking at the world." Vice President and Nobel Laureate Al Gore, New York Times, Wednesday, June 21, 2000, discussing some of the "big think" questions that intrigue him.

Generating Fractals with emphasis on Iterated Function System (IFS)

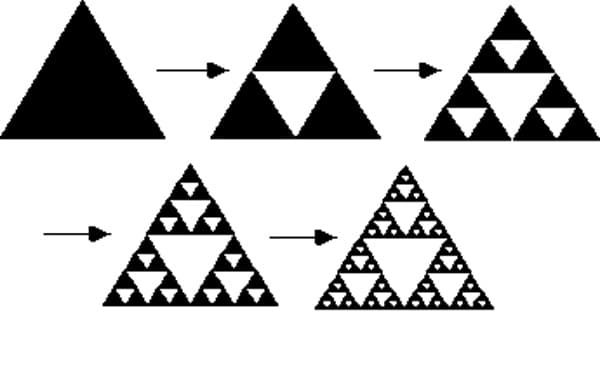

Fractals can be created in a variety of ways. One way is IFS, defined above, whereby the resulting fractal is self-similar.-. This unit will focus on drawing and computing fractals in 2D. Two dimensional (2D) fractals consist of copies of the original shape being altered by a function. A perfect example is the Sierpinski triangle. The functions make the shape smaller by connecting the points. Therefore the shape of an IFS fractal is made up of an assembly of smaller copies of itself, with each smaller copy also having an assembly of smaller copies of itself to infinity. This makes it a self-similar fractal.

Wac?aw Sierpi?ski's triangle is one of the simplest of geometric images. His triangle may also be constructed using a predictable algorithm. Predictable algorithm in the sense that we know what the output is supposed to resemble and hence given any size triangle, we can still produce the Sierpinski Triangle. To see this, we begin with any size triangle. Then we find the center of each side and use it as the tip of a new triangle, which we then cut out from the original triangle. What we are left with here, are three triangles each having an area which is exactly a quarter of the original and whose dimensions are one-half of the original triangle. Also, all the resulting triangles we created look exactly like the original. This process can ne continued to infinity and the same copy of the triangle will be created, it just gets smaller and smaller. That is, from each remaining triangle we remove the "middle" leaving behind three smaller triangles each of which has dimensions one-half of those of the parent triangle (and one-fourth of the original triangle). So should you just follow the process, for say 2 stages, clearly 9 triangles will remain at this stage. At the next iteration, 27 small triangles, then 81, and, at the Nth stage, 3 N small triangles remain. See figure 2 below.

At this point some students will ask, why do the triangles appear in powers of 3? The explanation will be because a triangle has only three sides and hence when we iterated, we got 3 smaller triangles from the original triangle. Should we have used a different shape that ended up giving us a different number of iteration other than 3 from its original, it would have been in powers of that number.

It is easy to check that the dimensions of the triangles that remain after the Nth iteration are exactly (1/3) N of the original dimensions (Figure 2).

Figure 3 Deterministic construction of Sierpinski's Triangle

Now, to help train the students' eyes to find fractal decompositions of objects, I will let them try to find smaller copies of each shape within the shape. I will show pictures of a tree, a snowflake, a lace, and or a fern and ask them to practice.

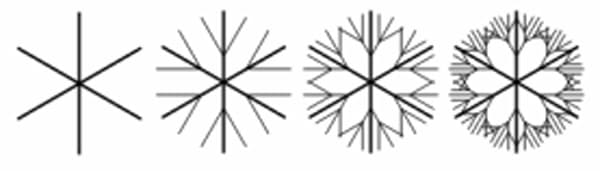

The concept used in Sierpinski's triangle can be used, with some changes, to develop other fractals that exist in nature. Look at the creation of the snowflake below. It is made from drawing six lines from the middle to their borders. Then two lines are drawn, this time, from each line. Continuing this process to infinity will leave you with a pretty picture like the one in figure 4 below.

Figure 4 Creating a snowflake using fractals

Initiators and Generators

Now that the students know how to find similar shapes within a shape, they can be introduced to the right process within self-similarity. Self-similarity is an elaborate way of saying to repeat a process over and over again. One way to realize self-similarity is to build the same shape within a shape and duplicate this algorithm infinite number of times. Each time realizing how the shape and the area being covered get smaller and smaller. This phenomenon is accomplished by two means. The initial action is the initiator and the second action is the generator. The initiator is the name given to the first item or original shape and the generator is the second and subsequent items. To realize this, let us look at figure 4 above. Here we are building a flake using the idea of initiators and generators. The initiator here is the 6 lines we drew from the center to the edge. While the two lines we drew over and over again, on the lines, are our generators. Therefore the key is this, substitute an image of the initiator with a magnified image of the generator making sure to indicate the direction where possible.

Measuring Fractals

The students in higher level classes should be ready at this point to move on to measuring fractals. There are a variety of procedures out there for measuring fractals. One effective way that I will introduce to my students is called the self-similarity dimension. Self-similarity dimension can only be used to measure fractals if the fractals posses self-similarity properties.

So if a fractal possesses self-similar property, then we can represent the number of self-similar pieces by a letter, say N. Lets also say these self-similar pieces increase by a scaling factor, say l. Finally, let us represent the dimension by a letter, say D. From the explanation of self-similarity above, we all agree that the scaling factor, l, increases exponentially. Therefore, it is safe to say that N =l D. Taking logarithm of both sides, we get, D =(log(n)/log(t)). Teachers of higher level math will be able to continue on with more complex shapes where the knowledge of logarithms will be useful.

There is a computer program called Winfeed which is a fractal examination software. With this program, the user is able to examine functional emphasis, including Mandelbrot and Julia sets, ferns and snowflakes, web and bifurcation diagrams, and more. With this program, all one has to do is upload the picture you are trying to calculate. Then hit a button and it automatically calculates the properties.

At this point, the students are better equipped to take on the development of fractal geometry in the lung. We will talk about the lung, its anatomy and physiology. Then look at an outline of the lungs and try to identify what type of symmetry exists there. Eventually, we will evaluate and measure the fractals that exist in them.

The fractal development of the lung

We already know that fractals help lungs develop. This means that lung lobes develop by splitting into smaller lobules. So the question to the students at this point is do the lungs continue splitting? Do they continue splitting to infinity? Is there an actual point when they stop splitting? How many lobules or smaller magnifications can there be? To answer these questions, we will look at the development of the human lung.

The development of a human lung is very confusing. It is broken into phases or stages. The first phase is the embryonic phase. In this phase, bronchial tree is laid out and the lung segments are defined. The next phase is the glandular or pseudo glandular phase. In this phase, bronchioles are formed. The next phases are the canalicular phase and the saccular phase. Branching and splitting occurs mainly in the embryonic phase and hence that is where our focus will be as a class.

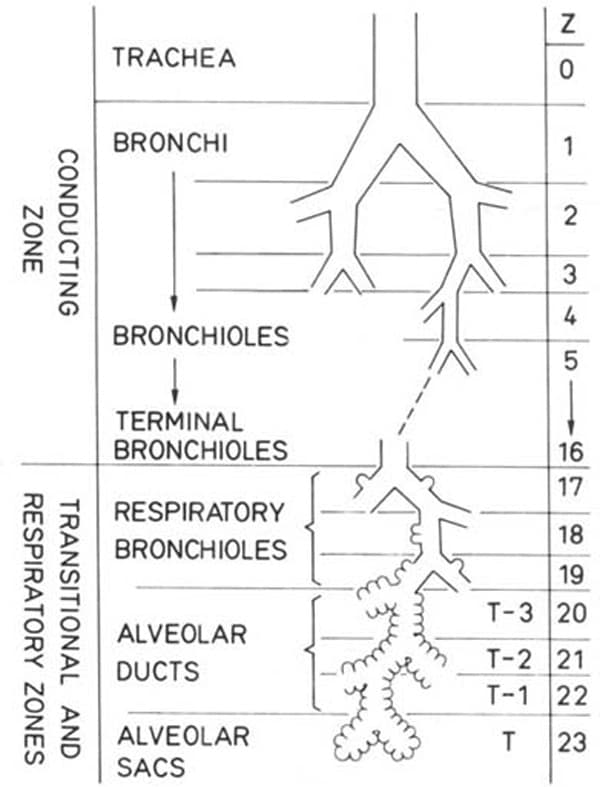

Figure 5 below shows the generation of the lung in the embryonic phase. It shows how branching at each generation phase. Let us give the generation phase a letter, say z. Since the branching of the bronchi and the notion of self-similarity are the same, we will not be wrong to say that the branching increases exponentially as well. If so then we can say at each generation phase, z, we get 2 z branches. In our lungs however, we can observe branches up to about 2 2 3

Figure 5. Fractal development in the lung

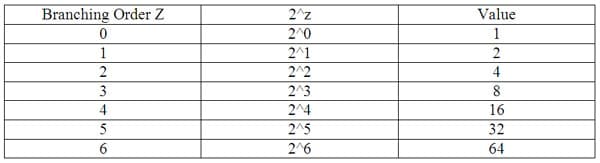

As the lung keeps branching and splitting from 0 to 1 to 2 and so on, it is doing so, in this case, in base two. Hence, 2 0 = 1, 2 1 = 2, 2 2= 4, and so on. This is also termed bifurcation. Bifurcation therefore is the separating of a body into two parts. In a human lung, the division continues up to a power of 23. That is 2 2 3 as seen in figure above. This is where the students will use their knowledge in powers and exponents to create a table of powers, so to speak. The table will be similar to the table below. The students will compute this manually all the way up to 2 2 3.

Importance of fractals in the lungs

Just as fractals can create magnificent pictures and designs so are they important in our lives. The existence of fractals in the lungs not only compresses the size of our lungs but also protect us from physical stress while they grow. Due to the compact nature of our lungs, thanks to fractals, our lungs are more efficient. The alveoli are the little air sacs in the lungs whose main task is to circulate oxygen in the blood. The time at which the circulation happens in the alveoli is directly proportional to the area of the alveoli in the lungs. Research shows that the surface area of an adult mammalian lung is750 sq ft and still they have a small volume.

As a whole, the lungs show properties of fractal geometry. Also, in the bronchi and bronchiole tubes, the property of bifurcation can be observed.

Comments: